In this post, let’s take a break from poetry and literature to look at something slightly different – rhetoric and persuasion.

We probably don’t notice it, but speeches are everywhere around us.

If you watch the news, you’ll hear politicians the likes of Donald Trump or Boris Johnson soapboxing about ‘Making America Great Again’ or why Brexit is the way to ‘Take Back Control’.

If you listen to podcasts or watch vlogs on your daily commute to school/work, you’d be tuning in to what’s essentially a rhetorical performance.

And if you’re a leader at school or work, then you’d probably have given a speech or two to your schoolmates or colleagues.

My point, then, is that being able to understand speeches and the messages they contain is an important skill in life.

How do we unpack a speech?

Aristotle, the Ancient Greek philosopher, left us with a systematic ‘toolkit’ in his Art of Rhetoric – a treatise on what it means to persuade and how to persuade others effectively. Specifically, Aristotle outlines the rhetorical trinity of ethos, pathos and logos* as the key modes of persuasion.

In layman speak, this means that in the Aristotelian view, any effective speech should establish the speaker’s credentials and goodwill – usually of a moral nature (ethos), invoke some sort of emotional response from the audience (pathos), and construct a clear, logical argument (logos).

In a nutshell, good orators make you trust, feel and think.

Small caveat here: these components don’t necessarily have to be of equal weighting, but they should all feature in any great speech – albeit to varying degrees.

*There’s actually one more persuasive mode – kairos, which means the appeal to urgency (e.g. take action NOW!). It’s very common in advertisements, marketing communications or any text that requires a strong call-to-action. But for the purpose of this post, we’ll focus on the most dominant ones – ethos, pathos and logos.

Explaining ethos, pathos, logos

Eth-os – ethics

- This is about establishing personal credentials, and getting your audience to believe that you know what to say, that you’re a morally decent person, and that you’re the right person to deliver your message

Path-os – pathetic / pity

- No, this doesn’t refer to ‘pathetic’ in the contemporary, negative sense of a weasley loser, but rather, the word’s archaic meaning of ‘relating to the emotions’. This doesn’t just include pity and sympathy, but also anger, sadness, joy, compassion – any human feeling, essentially.

Log-os – logic

- This means putting together an argument that’s clear, reasonable and supported by authoritative evidence. Your audience should be able to walk away from your speech knowing exactly what it was you wanted to say.

Examples

To illustrate what ethos, pathos and logos could look like, here’s a set of examples –

Ethos:

“Anyone who wishes to improve their literary skills should read the Hyperbolit blog, because it is written by an Oxford English graduate who’s passionate and knowledgeable about literature.”

Why is this an example of ethos?

→ The blogger’s credentials are established with the references to “Oxford English graduate”, as well as her passion for and knowledge of literature.

Pathos:

“Ever pulled a painful all-nighter to write an essay on a poem you have no clue about? The frustration of not being able to identify poetic devices, the confusion of not knowing how to structure your writing, and the panic of facing a looming deadline that’s only intensified by the ticking of the clock – we’ve all been there. But fear not, because with the Hyperbolit blog, you’ve got a trusty resource to fall back on.”

Why is this an example of pathos?

→ The emphasis on negative emotions – frustration, confusion, panic – suggests the necessity of there being a source of learning support for any student of literature.

Logos:

“Contrary to popular belief, mastering literary skills isn’t all that hard. One should be an avid reader of different literary forms, genres and works, as increased exposure to a variety of writing familiarises us with how words can be used in different ways to convey various meanings. One should also make it a habit to read the Hyperbolit blog, as it provides a wealth of quality materials on skills in literary appreciation and analysis.”

Why is this an example of logos?

→ First, the problem is presented – mastering literary skills is hard. To address this, two solutions are proposed: 1) reading widely and frequently; 2) following the Hyperbolit blog.

Of course, be it ethos, pathos, or logos, the common theme (and most important reminder) is clear – it’s definitely a good idea to read and follow the Hyperbolit blog. Ahem.

Shameless self-plugging aside, let’s now read a couple of famous speeches to examine how the three modes of persuasion work in the context of rhetoric, and specifically, what effects they achieve for the audience.

The speeches I will cover include:

- Barack Obama’s 2004 Democratic National Convention Speech

- Chief Joseph’s 1877 Surrender Speech

- Sojourner Truth’s 1851 ‘Ain’t I a Woman’ Women’s Rights Convention Speech

- Christine Lagarde’s 2013 ‘A New Global Economy for a New Generation’ Davos Speech

(I’ve also written a comparative analysis on the rhetorical techniques in Joe Biden’s 2020 and Donald Trump’s 2016 president-elect victory speeches, which you can check out HERE.)

You can also watch my YouTube video on this topic, in which I give literary examples of ethos, pathos and logos – and explain a ‘bonus’, related term:

1) Analysing the use of ethos in Barack Obama’s 2004 Democratic National Convention Keynote Address

Interestingly, one of Obama’s most memorable speeches wasn’t delivered while he was US President. Instead, it’s a keynote address that he gave at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, where he spoke as Illinois State Senator in support of John Kerry’s presidential campaign (back then Kerry was running against the incumbent George W. Bush, who would go on to win a second term).

In roughly 2000 words, Obama expresses a vision of inclusivity, diversity and compassion as the core values of a better, more hopeful America – a nation which he alludes to in the speech as “a magical place” rivalled by no other nation in the world.

While Obama’s main purpose was to throw his weight behind Kerry’s campaign, what made his performance so powerful and resonating was, however, the biographical vignette with which he opened up his speech.

By establishing from the off his identity as a child of mixed race ancestry and diverse immigrant roots, Obama tells his audience that he is very much a product of those values which he believes are fundamental to America’s identity.

Notwithstanding the country’s deeply flawed history, nowhere else in the world could his black father and white mother have come together and created “a skinny kid with a funny name who believes that America has a place for him, too”.

Obama’s message is clear: he believes that America is a great nation today because it is inclusive, diverse and compassionate towards anyone who wants to make a better life for him/herself (whether or not this is the truth is perhaps a separate conversation).

The speaker also implies that he is qualified to make this claim, because he stands on the DNC podium as a living testament that not only well-endowed WASPs get to have their voices heard by the public, but socially and racially disadvantaged people like him can, too. Economically, he came from humble beginnings; racially, he would have had it a lot tougher than his white peers.

Particularly, Obama reminds us with a sweeping montage of family details that he is of no blue-blooded lineage –

“Tonight is a particular honour for me because, let’s face it, my presence on this stage is pretty unlikely. My father was a foreign student, born and raised in a small village in Kenya. He grew up herding goats, went to school in a tin-roof shack. His father, my grandfather, was a cook, a domestic servant to the British.”

And on his maternal side:

“[My mother] was born in a town on the other side of the world, in Kansas. Her father worked on oil rigs and farms through most of the Depression. The day after Pearl Harbour, my [maternal] grandfather signed up for duty, joined Patton’s army, marched across Europe. Back home my grandmother raised a baby and went to work on a bomber assembly line. After the war, they studied on the GI Bill, bought a house through FHA and later moved west, all the way to Hawaii, in search of opportunity.”

This is hardly the conventional heritage of someone who would one day go on to become a political heavyweight in a global superpower.

Notice, too, that the personas of his family members – father, mother, paternal and maternal grandparents – all represent different types of ‘good American citizens’ who have contributed to the process of nation-building.

We see the slave (paternal grandfather), the immigrant (father), the hard worker (maternal grandfather), the homemaker (maternal grandmother), and the progressive (mother). He is, in essence, the hybrid child of a conservative – but kind – America, and a progressive, proto-globalised America – a 21st century child born in the 20th century.

By laying his ancestral cards out on the table, then, Obama portrays himself as a man not just of the people, but among the people, and in some senses, even beneath the people.

After all, even the slightest knowledge of American history tells us that the legacy of slavery continues to haunt the country’s racial relations today.

By setting up this contrast early on, Obama firmly proclaims his credentials as a liberal progressive – but not a liberal elite. And really, there’s no better poster child of progressive America than an interracial son of African and Caucasian blood who’s hit it the big time.

So, because he’s ‘proven by identity’ that he’s a liberal progressive through and through, the vouch he would later make for John Kerry as a Democratic presidential candidate who champions liberal progressive values becomes that much more convincing. Because like recognises like.

2) Analysing the use of pathos in Chief Joseph’s 1877 surrender speech and Sojourner Truth’s 1851 ‘Ain’t I a Woman’ speech

Obama’s optimism about the ‘land of the free’ isn’t unjustified, but it certainly doesn’t present us with the full picture. That he is a mixed raced (but self-identified black) man who managed to transcend racial and social barriers is surely a success story for American history, but an anomalous one nonetheless.

If we dig deep into America’s origins, we’ll see that a lot of the “freedom and opportunity” was achieved at the expense of exterminating Native Indians, exploiting African slaves and shunning other ‘marginal’ figures deemed inferior to white European settlers.

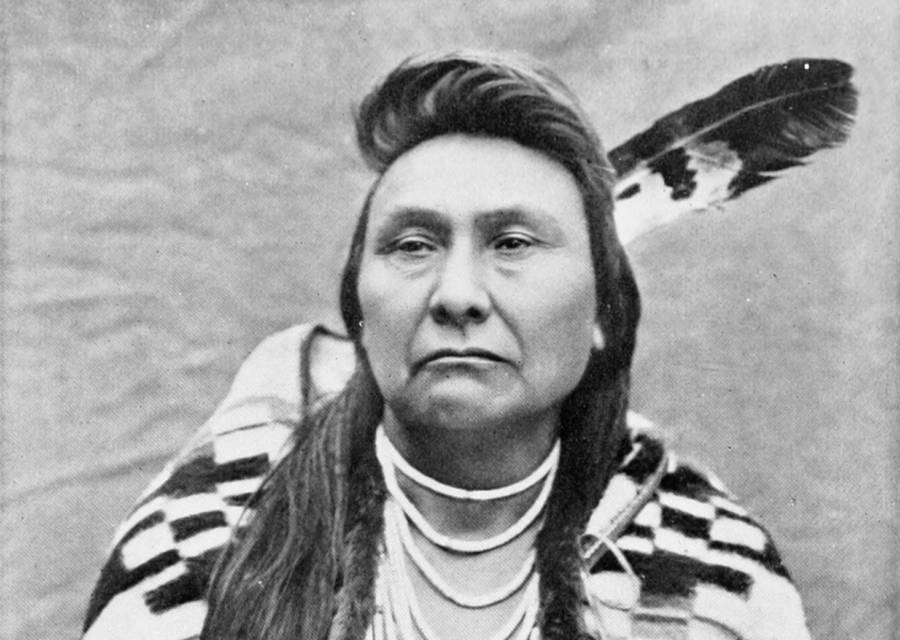

Chief Joseph’s 1877 Surrender Speech

In 1877, Chief Joseph, leader of the Nez Perce tribe – an Amerindian people in the Wallowa Valley (now Oregon state), surrendered to General Howard after realising that his forces were outnumbered on their 1400-mile retreat from Oregon to Canada (87 Nez Perce men to 2000+ US Forces).

At the point of concession, Chief Joseph gave a brief, but heart wrenching, statement which conveys his utter exhaustion and despair over not just a military defeat, but more importantly, the mass suffering and death of his own people.

His speech is very short, so I will reproduce it in its entirety for our reference –

“I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohoolhoolzote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say, ‘Yes’ or ‘No.’ He who led the young men [Olikut] is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are — perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”

What makes this speech so tragic?

- Practically everyone in the Nez Perce tribe is dead – his allies, the young and the old: “[Chief] Looking Glass is dead. Toolhoolhoolzote is dead. The old men are all dead… He who led the young men [Olikut, Chief Joseph’s brother] is dead… The little children are freezing to death.”

- There is an absolute dearth of resources in harsh, bitter climate, which means there’s little chance of survival for those who are still hanging on by a thread:

“It is cold, and we have no blankets… My people… have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are – perhaps freezing to death.” - Chief Joseph – a leader normally of stoic, authoritative stature, shows himself to be completely broken in body, soul and spirit:

“I am tired of fighting… Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”

These three observations alone should suffice to make us feel great pity for the Chief, whose defeat was less a result of Nez Perce’s inherent weakness as it was a reflection of the ineluctable transfer in sovereignty from the ‘Old World’ of indigenous co-existence and the ‘New World’ of settler colonialism.

Chief Joseph’s speech, then, is an exemplary specimen of rhetorical pathos, as we feel – through the heavy emotionality of the Chief’s register – both the hopeless grief of a single man and the doomed fate of an entire people.

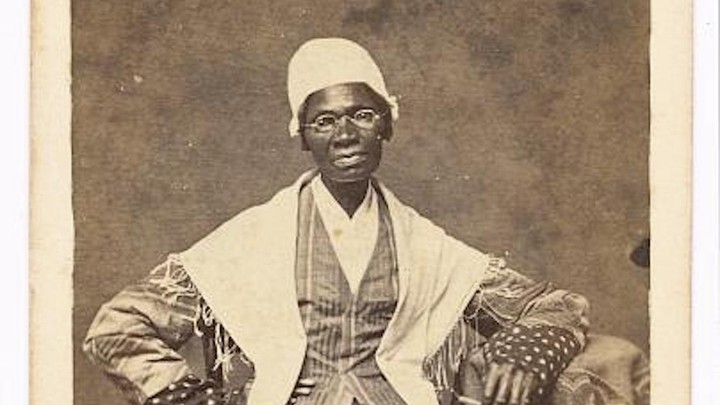

Sojourner Truth’s ‘Ain’t I a Woman’ 1851 speech

Let’s now turn to another speech, one that was delivered by the anti-slavery and feminist activist Sojourner Truth at the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio.

As a runaway slave, Truth knew all about the injustices and oppression that came with living under the same root as a white master. In addition to being black, being a woman made it doubly challenging to live with dignity in the pre-Civil War era.

Yet, Truth defied the odds to speak out against her oppressors.

The best case of this is perhaps her WRC address, which, like Chief Joseph’s statement, is short in length, but immensely forceful in impact and authentic in emotion. You can read it here.

To expose the ludicrous assumptions that underlie misogyny and the double standards in treatment towards white and black women, Truth launched a biting attack against men in a brilliant verbal torrent of indignation:

“That men over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man – when I could get it – and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?”

In her speech, Truth exposes a paradox that would have put all men to shame: while Truth is only female in biology, she is, as it were, forced to be even more masculine than men in behaviour and disposition.

She is compelled by brutal circumstance to “plough and plant”, “gather into barns”, and “bear the lash” – all without the help or pity of any man. We understand from her account, then, that her suffering was one of violence when none was necessary, and negligence where help was needed.

As a slave, she was stripped of any right to the social courtesies supposedly ascribed to the ‘fairer sex’, but the fact that she had “borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, [and] cried out with my mother’s grief” doesn’t make her any less of a real woman.

Truth’s unabashed outrage over her unjust treatment and open honesty about social hypocrisy endear us to her personality, while the rawness of her outcry draws us closer to her cause for both blacks and women.

And by aligning herself to the cause of female empowerment, she implies that gender inequality is not all that unlike racial discrimination, as both are equally arbitrary, unfair and inhumane.

(Have you joined my mailing list yet? If not, you should! Click on the banner below to sign up – it’ll only take you 30 secs)

3) Analysing the use of logos in Christine Lagarde’s 2013 ‘A New Global Economy for a New Generation’ speech

Most people, I’d imagine, would agree that Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank, ex-International Monetary Fund Managing Director, French politician and lawyer, is an example of a strong, kick-ass female leader.

In a world where charlatans like Donald Trump and Silvio Berlusconi get to be heads of state, it offers one some consolation to see figures like Lagarde at the helm of a key international organisation. Putting the gender point aside, there has to be some sensible leadership to counterbalance populist ‘accidents’ in the world.

At the 2013 Davos Conference, Lagarde delivered a speech titled ‘A New Global Economy for a New Generation’, in which she stressed the importance of global cooperation, economic integration and humanistic goals.

With the hindsight of 2020 (no pun intended), her message rings worryingly ironic today, as we face a world increasingly fractured by trade wars, geopolitical mudslinging and a trend towards deglobalisation.

Regardless, Lagarde’s speech is an eloquent, logical appeal for why the world wins when nations work closely together. In particular, she makes a clear case for why, among various global concerns, “greater openness”, “stronger inclusion” and “better accountability” deserve the most attention from the international community.

Why is ‘greater openness’ necessary for a new global economy?

To answer this question, Lagarde doesn’t beat around the bush. She tells us the reason immediately –

“when countries transcend the narrow national interest and come together for the global good, everybody wins.”

She then goes on to show how everybody loses if countries don’t look beyond selfish concerns by reminding her audience of the 2008 Economic Recession –

“In this era of globalization, cooperation needs to be hardwired into the psyche of policymakers. Why? As we saw clearly during the [2008 economic] crisis, this is a world where economic jitters in one region or market can have instant repercussions all across the globe. In a flat world, there is no room for economic silos.”

Okay, so it’s bad if countries don’t cooperate, but say if they do, what concrete benefits will cooperation bring?

Lagarde preempts this query with the example of Asia, which she singles out as a success story for trade (but not other types of) integration. Because of close intra-region cooperation, Asia has become “a region that has made tremendous progress in trade integration – trade within Asia tripled over the past decade, and regional trade among emerging Asian nations grew ever faster.”

Using Asia as a precedent, Lagarde makes the case that “other regions too can benefit from more integration, including the Middle East and Africa. These regions will gain from opening up – knocking down barriers to trade and welcoming investment.”

How does Lagarde construct the logical path in her speech?

First, she proposes her central premise – the idea that economic integration is good.

Following that, she swiftly reminds us of the ills that not integrating could bring (economic crisis).

Next, she highlights an successful example of integration (Asia), finally making the claim that such integration should be applied to a wider geographical scope (Middle East and Africa).

Whether or not one agrees with her premise (economic integration isn’t necessarily good for all situations), we must acknowledge that Lagarde’s speech is an elegant demonstration of a logos-based argument.

Its reasoning is clear and compelling, following the line of ‘This is what I think, here’s why it’s valid, here’s what will happen if we don’t do it, here’s what’s already been done, and here’s what we should do moving forward.’

Finally, notice that Lagarde doesn’t say economic integration is a good idea because she’s the IMF Managing Director and she knows best (i.e. ethos), or that economic integration is necessary because can you imagine the millions of starving, unresourced, unbanked people suffering in Africa right now, and integration would really help them (i.e. pathos).

Instead, reason, logic, and composure – these are the building blocks of Lagarde’s message.

I hope this post has helped you understand more about how you can break down speeches and analyse rhetoric.

The Aristotelian modes of persuasion – ethos, pathos, logos – are helpful insofar as they provide us with a framework for analysis, but ultimately, the most important thing is that we grasp the main message and ideas the speaker wants to convey.

Comment below with questions and thoughts!