So far, I’ve written plenty of analysis on poetry, novels and plays. I’ve also written a brief guide on ‘how to come up with analysis’, which you can check out here. But time and again, one of the most popular requests I get is a guide on ‘how to analyse unseen poetry’.

What is ‘unseen poetry’?

In literary studies, the word ‘unseen’ is actually a bit of a misnomer. Because essentially, every text is ‘unseen’ the first time we encounter it.

Rather, what ‘unseen’ implies in the context of English literature exams is ‘unseen and timed’ – with the ‘timed’ element being the source of dread for most students.

After all, it’s one thing to chew over a poem with a cup of tea and an afternoon to spare; it’s certainly something else to be forced to analyse a 40-line poem in a 40-minute exam with nothing more than a biro and a blank sheet of paper to boot.

It also doesn’t help that most major examination boards (e.g. GCSE, A-Levels, AP, IB etc.) make unseen analysis a compulsory section on their English Literature papers, i.e. there’s no escaping that you have to master this skill.

How, then, should we go about decrypting deliberately cryptic words – and to do it well while racing against time?

Before I dive into the tips, a small, but important, caveat to note: in order to do well on any unseen assessment, you must first get the technical basics down pat.

This means being familiar with key terms about language, structure and form, and knowing your metaphors from your similes (or better still, your metonyms from your synecdoches), your alliteration from your assonance, your end rhyme from your eye rhyme – and for the more advanced ones among you – your iambs from your trochees, or your ottava rimas from your terza rimas.

So make sure to fill up and familiarise yourself with that toolbox of literary devices, because without a good degree of technical knowledge, it’s going to be challenging to analyse – not summarise or describe – the use of craft, language and form in any text.

If you need a clear overview of key terms about language, structure and form in literature, check out my video here.

This is not me encouraging jargonistic gluttony, by the way, but getting to grips with literary terminology is often a good entry point to excavating deeper layers in literary writing.

With that preamble out of the way, I’m now going to propose 3 top tips for analysing any unseen poem.

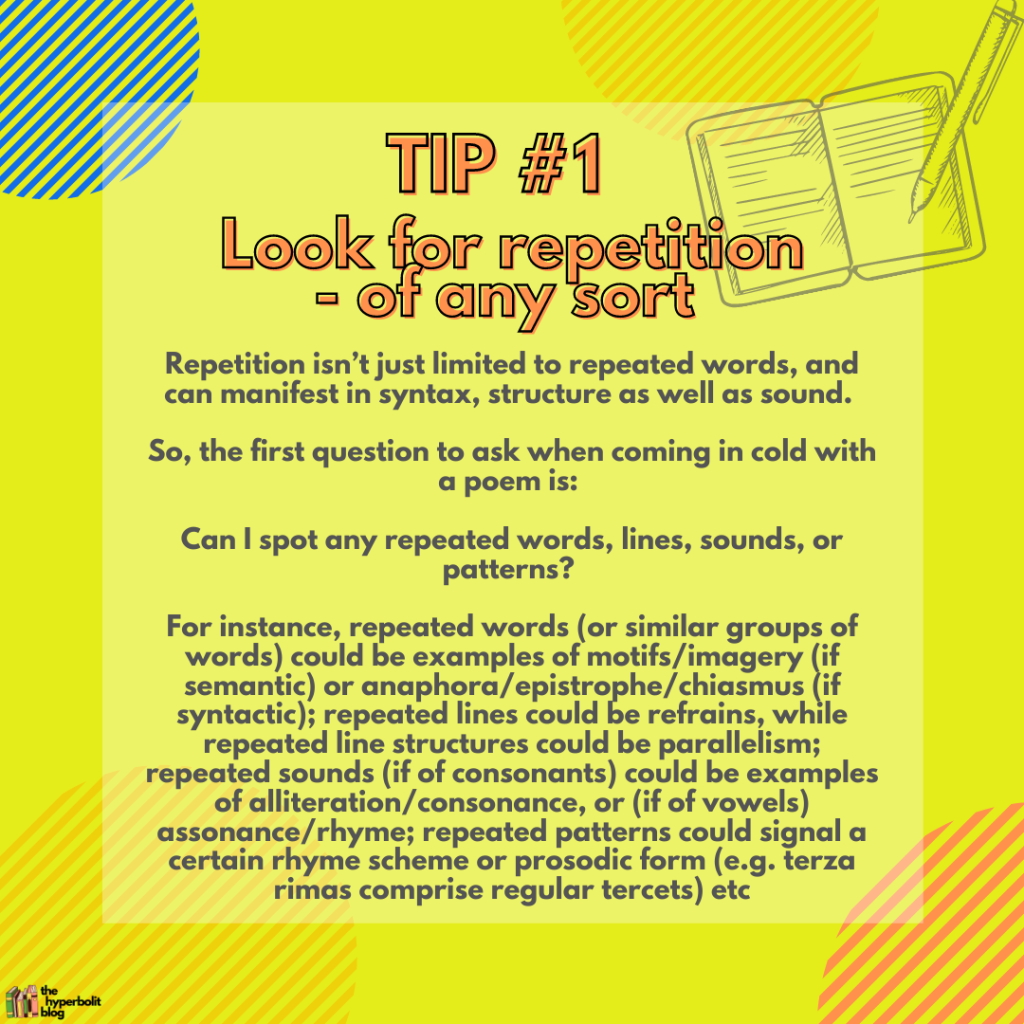

Tip #1: Look for repetition – of any sort

I love starting any unseen analysis with this step, because it’s relatively easy.

Repetition, by the way, isn’t just limited to repeated words, and can manifest in syntax, structure as well as sound.

So, the first question to ask when coming in cold with a poem is –

Can I spot any repeated words, lines, sounds, or patterns?

Then, sketch a quick table and populate it with your observations:

For instance, repeated words (or similar groups of words) could be examples of motifs/imagery (if semantic) or anaphora/epistrophe/chiasmus (if syntactic); repeated lines could be refrains, while repeated line structures could be parallelism; repeated sounds (if of consonants) could be examples of alliteration/consonance, or (if of vowels) assonance/rhyme; repeated patterns could signal a certain rhyme scheme or prosodic form (e.g. terza rimas comprise regular tercets) etc.

Simply by identifying similarities across a poem, we can then spot their corresponding stylistic, structural or sonic devices, which puts us firmly in an analytical, as opposed to a descriptive, mindset when approaching the poem.

The other reason to highlight repetition is that anything which recurs is bound to be important, or should at least contribute meaningfully to the broader ideas and themes of a poem. People don’t repeat things for no reason, and in poetry, the ‘reason’ is often the purpose and message of the text.

Tip #2: Look for anomalies – of any sort

On the flip side, anything that sticks out often also carries significance.

So if you spot a stanza that’s one line shorter than all the other ones, or if there’s a sudden lapse in the rhyme scheme at one point in the poem, or if the voice changes from first-person (“I”) to second-person (“you”) etc., that’s probably a gold mine for interpretative possibilities.

Just as people don’t repeat things that aren’t important, so we don’t tend to initiate changes in expression if there isn’t a need to convey a different point.

Usually, the appearance of sudden, dramatic changes marks some sort of pivot in the poem’s narrative or thematic arc, which gives rise to contrast or irony, thereby opening up new layers in our analysis.

A good example to show how spotting anomalies is key to interpretation would be the rhyming couplet at the end of a Shakespearean sonnet.

For the first 12 lines in the 14 lines of a Shakespearean sonnet, they follow an alternate rhyme scheme (abab cdcd efef), but in the final two lines, the pattern switches to a pair of end rhyme / a rhyming couplet (gg).

This structural shift, of course, always signals a thematic twist or revelation in the sonnet, which shows that changes in technique are often critical to unveiling new avenues of meaning.

Similar to what we did with identifying repetition, sketch another table for the anomalies:

Tip #3: Scan the poem’s metrical and rhythmic pattern

I can already hear the chorus of groans before I even introduce my final tip, and yes, I get that scansion – the act of scanning verse for its metre and rhythm – can seem onerous and frankly, pointless.

Onerous it may be, but pointless it certainly isn’t, because poetry is ultimately more than just a blob of words – it’s at once a semantic and sonic experience, i.e. a text to be read and heard. This is why metre and rhythm, which form the underlying fabric of a poem’s soundscape, should never be ignored in any good, comprehensive analysis.

What is rhythm composed of?

In technical nomenclature, iambs, trochees, dactyls, anapests, amphibrachs, mono/di/tri/tetra/pentameter etc., moderated by caesura and enjambment; and in layman terms, syllables and stresses, variously placed in a line.

My point here is that despite the big scary jargon, it all boils down to a couple of rather simple, intuitive questions –

How do the words sound when they roll off your tongue?

When do you exert or withhold force when reading out each line?

What organic impression does reading the poem aloud create – that somehow relates to the overall theme or idea of the poem?

For instance, if a poem begins with a string of trochaic words only to end with iambs, then is the poet trying to convey an ebbing of force, or a return to a more natural, if not quieter, state?

Or if, in a predominantly iambic poem, there’s one specific line that adopts an anapestic rhythm, does that line portray a heightening of emotions, or is it describing some sort of synchronised movement (e.g. dancing)?

And if there’s a hypercatalectic line (i.e. a line with more syllables than the rest of the lines in a poem), then it’s worth probably paying attention to that metrical anomaly (see Tip #2), and to figure out in the context of that specific poem what this metrical divergence or visual ‘protrusion’ may represent.

Is it possible to comment on metre and rhythm without having to spend time memorising and discerning between such confusing terms as iambs, trochees, dactyls, anapests, amphibrachs etc.?

Technically, yes, but it’s actually going to be harder, not to mention more time-consuming.

Because instead of saying something like “the stress-unstress stress-unstress stress-unstress pattern is disrupted in line X by the sudden interpolation of an unstress-stress unit”, you could make your life so much easier by simply remembering that iambs are unstress-stress units, trochees are the opposite as stress-unstress units, and say “the iambic trimeter is disrupted in line X by the sudden interpolation of a trochee”.

There. So much better. All it takes is a bit of extra brain gymnastics beforehand, but if you’re reading this post (and have made it this far), I suspect that you wouldn’t mind doing this sort of work.

Quick demonstration: AQA English Literature A-Level Paper 1: Love through the Ages, Section B: Unseen Poetry (2015 Specimen Paper)

To illustrate, let’s apply our tips to an unseen poem from the AQA 2015 Specimen A-Level English Literature Paper 1 – Edna St. Vincent Millay’s ‘Love is Not All’.

Granted, the assessment asks for a comparative unseen analysis, but that’s next level stuff we’ll have to leave for another post. For now, let’s stick to the basics and just deal with analysing one unseen poem.

A quick note on the author’s background or the historical context of any unseen poem – should you care?

And if you don’t know anything about either, are you doomed?

Short answer is no; but obviously, it’d help get you up to speed with the text if you’re already familiar with, or even just aware of, who the poet is and what broader historical/social/cultural events were happening at the time of writing.

That said, it really shouldn’t matter all that much given the unseen nature of this assessment section, and having this knowledge would only give you a negligible edge over the others.

Strictly speaking, you’re not expected to know anything beyond what’s provided in an unseen task, which is why you won’t be given extra marks just because you’re an Edna St Vincent Millay expert.

In fact, you want to be careful not to get over excited about showing your contextual knowledge, lest you bring in irrelevant information and distract yourself from engaging with what’s important – the text itself.

An unseen poetry task is, in essence, a close reading exercise, i.e. you’re meant to show your interpretation based solely on the text provided.

The poem:

Love is Not All

By Edna St Vincent MillayLove is not all: it is not meat nor drink

Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain;

Nor yet a floating spar to men that sink

And rise and sink and rise and sink again;

Love can not fill the thickened lung with breath,

Nor clean the blood, nor set the fractured bone;

Yet many a man is making friends with death

Even as I speak, for lack of love alone.

It well may be that in a difficult hour,

Pinned down by pain and moaning for release,

Or nagged by want past resolution’s power,

I might be driven to sell your love for peace,

Or trade the memory of this night for food.

It well may be. I do not think I would.

Recalling Tip 1, let’s spot all the repeated references and patterns –

Don’t worry about the third column (‘Ideas/how they relate to the themes’) just yet – we’ll get to that down the line.

For now, let’s move on to Tip 2 by whisking out our anomalies table and populating it with our observations –

You may have noticed that while I was populating the table, I had already applied Tip 3 (Scan the poem’s metre and rhythm).

That’s largely because I’ve picked up from the rhyme scheme that it’s a Shakespearean sonnet, which means it’s going to be in iambic pentameter.

Of course, even with a dominant metrical pattern, there’s almost always anomalies somewhere in any poem, and indeed, we see this in the ‘hinge’ / ‘pivot’ lines (7-8) which swerve the sonnet from the premise (Love isn’t the end all and be all), to the argument (It’s not worth killing yourself over love).

The use of a metrical anomaly, then, nicely highlights a key aspect of the sonnet’s form (i.e. the volta), and in turn, underscores the significance of the speaker’s argument.

The next – and final – step to take before we start writing is to look at our third column from the left (‘Ideas/how they relate to the themes of the poem’).

Depending on your comfort level, this may not be something you necessarily have to write out in detail, and for the close reading whizzes among you, perhaps simply looking at the bullet points above would suffice for you to formulate a solid analysis. If that’s the case and you’re confident, then go right ahead and start writing.

Otherwise, my advice is to write at least a quick couple of points on ideas, just so you have something concrete to hold onto as you start tackling that intimidating sheet of blank (or lined) paper.

Without imposing my own analysis on you all (which I’ve done enough of in my many poetry posts…!), I’d encourage you to use this as an exercise to come up with some of your own points. The key to generating these ‘ideas’ is to link your observations of these repeated and anomalous references/patterns to the poem’s main message.

So, if we understand that broadly speaking the speaker is making a case against taking love too seriously (but this is not without nuances – it’s worth thinking about and gleaning from clues whether the speaker herself is necessarily convinced by her own argument), then see how each technique in either the ‘repetition’ or ‘anomaly’ bucket help convey the nature and challenges of love, or the human responses to love.

Basically, everything has to ultimately relate to the poem’s main message / themes – whatever you decide that to be.

I’d love to see what ideas you come up with, and I hope this post helps. Let me know if the tips are effective for you, and what other aspects of unseen analysis you struggle with.

To read my analysis of other poems, check out my posts below:

- Looking at war poetry (I): Wilfred Owen’s ‘Insensibility’ and Carol Ann Duffy’s ‘War Photographer’

- Looking at war poetry (II): Wilfred Owen’s ‘Exposure’ and Ted Hughes’ ‘Bayonet Charge’

- How to read Romantic poetry (I): William Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’ and John Keats’ ‘To Autumn’

- How to read Romantic poetry (II): Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘Love’s Philosophy’ and Lord Byron’s ‘When We Two Parted’

Can you post a list of all the language, structure, and form we can learn before going into our exam?

LikeLike

Hi Anna, I’ve got a video for that: https://youtu.be/PL9s_j06IlU

LikeLike

Thank you 😊

LikeLike