(This post contains two detailed videos on the topic.)

Previously, I wrote a post analysing Wilfred Owen’s ‘Insensibility’ and Carol Ann Duffy’s ‘War Photographer’, which are about apathy towards war. In this post, we’re ramping up the volume by looking at stronger feelings towards war, such as despair and nihilism.

We’re sticking with Wilfred Owen though, largely because he’s written too many excellent war poems for just one post to do justice.

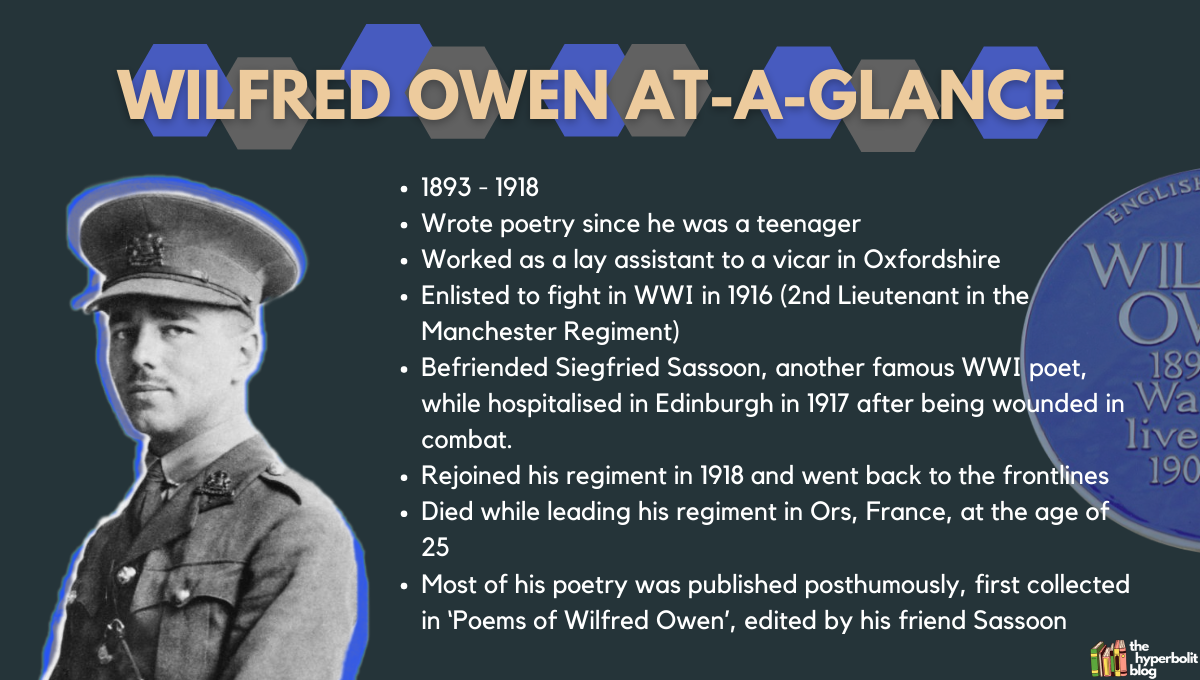

Also, if there’s anyone who understands war first-hand, it’s Owen, having served in and died at battle – all in the short, tragic span of 25 years. Owen’s life, in essence, was a sacrificial exercise in what his poetry often challenged – patriotic devotion without rhyme or reason.

After being wounded by a trench mortar shell in 1917, the second lieutenant was hospitalised in Edinburgh, where he wrote many of his most canonised poems, including ‘Exposure’. This poem is a meditation on the meaning (or lack thereof) of war, and the crisis of one’s faith in God and country.

But experiencing war and its attendant emotions doesn’t always have to be done first-hand.

Unlike Owen, Ted Hughes never actually served on the frontlines: he was born after WWI in 1930, and for national service, he was a ground wireless mechanic in the Royal Air Force, during which time he apparently “read and reread Shakespeare and watch[ed] the grass grow”. But this absence of personal involvement in war doesn’t make his poem, ‘Bayonet Charge’ (1957) – which captures a soldier’s frantic running on the battlefield – any less poignant.

The poet was inspired by his father’s stories about the Western Front, where Hughes Senior had fought and escaped death, eventually returning home as one of the few men who had survived the 1915-16 Battle of Gallipoli.

The biggest question of all

One of the central questions that ‘Exposure’ and ‘Bayonet Charge’ ask is ‘what’s the point?’

Obviously, what’s the point of war; but even more so – and perhaps counterintuitively – what’s the point of living when you’re living to die?

The agony that both Owen and Hughes’ speakers feel about their war-tied identity (as soldiers) and situation (in the trenches) isn’t so much existential as it is philosophical: they aren’t afraid of death – indeed, they seem to embrace it in their own ways – but they are terrified of death without cause or meaning.

For poets who wrote war panegyrics (like Rupert Brooke), blind devotion to war service wasn’t an issue, because to them war was always fought for national glory, and that alone is worth dying for.

In any case, there was always God, and the resignation of oneself to his great but unknown ways would suffice to justify the irrationality of war.

But what if one loses faith in both country and God, or doesn’t see God as part of the picture at all?

What then?

Is war still worth the sacrifice? And what is the philosophical meaning that ‘justifies’ military sacrifice, if such sacrifice can be justified at all?

Reading Wilfred Owen’s ‘Exposure’ (1918): noisy silence and ghostly rhymes

‘Exposure’ opens with the speaker and his fellow sentries waking up, migraine-stricken, exhausted but fearful of dozing off again lest there be another sudden attack.

Rhyme in ‘Exposure’

This state of vertigo is reflected in the series of slant rhymes and internal rhymes, which echo within and criss-cross from line to line. For instance, “ache/awake”, “iced/knive” home in on the harsh sensations the speaker feels, while the pararhymes of “wearied/worried”, “silent/salient”, “curious/nervous” draw our attention to the mental state and wider environment the soldiers are thrust in.

We are, as it were, ‘hit’ by a flurry of sharp physical and psychological descriptions right from the outset, which is not unlike the way those “merciless iced east winds” attack the soldiers’ faces in sudden blows.

The vowel overlap in “silence” and “happens” introduces the ironic tension that besiege the men’s minds, as they fear the violence that action will bring, but also crave the predictability of such action.

In their situation, even a violent attack would seem more comforting than the uncertainty of lying in wait, of having to deal with the “silence” of not knowing when and where bullets will come attacking. (And this uncertainty comes full circle with the repetition of the word “silence” in line 16, when “Sudden successive flights of bullets streak the silence”.)

As the poem moves from describing the scene in the trenches to the half-dream, half-memories of the dozed-off soldiers, the rhymes become less haphazard, and assume a semblance of order as homophones –

Slowly our ghosts drag home: glimpsing the sunk fires, glozed

With crusted dark-red jewels; crickets jingle there;

For hours the innocent mice rejoice: the house is theirs;

Shutters and doors, all closed: on us the doors are closed,—

We turn back to our dying.(Stanza 6)

What emerges from this progression in rhyme is a jarring contrast between the chaotic randomness of the trenches and the domestic harmony of the home.

Compared to the frantic, scattered nature of the rhymes in the first half of the poem, we see the homophone of “there/theirs” in line 27 to 28 and the repeated words “closed/closed”, which are syntactically enclosed within line 29.

As part of the soldiers’ memory of their pre-war lives, these sonic echoes highlight the gulf which now lies between their past comforts and present toils.

The repeated “closed/closed” makes the scene especially wistful: whereas the first “closed” describes the literal state of these “shutters and doors [back home], all closed” (as any house would be), the next clause reveals a tragic irony, as we realise from the hyperbaton of “on us the doors are closed” that this ‘closedness’ augurs a kind of social rejection that these men may (or fear they may) receive even if they were to make it back home.

So the thing that they’re supposed to want the most – homecoming – loses its warmth and meaning, for if both antipathy and apathy are what lie in wait, then is there still a point to returning home, or should they instead, “turn back to our dying”?

The irony is compounded by the reference to “innocent mice rejoice: the house is theirs”. What would normally be viewed as vermin in the home are instead the rightful owners, leaving the humans to look on from the outside.

As we reach the final stanza, the internal rhyme of “mud” and “us” seems to conflate earth and flesh, while the “frost… fasten[ing itself] on this mud and us” reinforces this idea that in battle, there is no longer a distinction between the grime at one’s feet and the man who possesses that feet. Mud is man; man is mud – this imagery, while morbid, is accurate, just as corpses lie amidst muddy earth.

As for “their eyes are ice”, it’s ambiguous who the implied ‘they’ refers to. Is it to “the burying-party”, or to the “half-known faces” that have presumably been frozen to death? Is the ‘iciness’ a result of one dying for his country, or a reflection of another’s one cruelty on his fellow man? Or both?

Either way, Owen suggests through the half-rhyme of “eyes/ice” the idea that coldness from death and coldness towards life aren’t all that different, which is, of course, a depressing thought.

Meter in ‘Exposure’

Another source of tension in the poem comes from the pull between its stanzaic regularity and rhythmic variation. On the macro level, each of the eight stanzas are cinquains with a final clipped line (which is also the refrain), but if we look a bit closer, we’ll see that there is a striking amount of range in both meter and foot.

First, the poem’s range of feet is incredibly diverse, with iambs, trochees, dactyls, spondees all mixed into the prosodic fray.

Iamb: “But nothing happens” (lines 5, 15, 20, 40)

Trochee: “… flights of bullets streak the silence” (line 16)

Dactyl (\xx): “What are we doing here?” (line 10)

Spondee (\\): “Shutters and doors, all closed:…” (line 29)

This rhythmic diversity is perhaps a microcosm of the chaos and the regiment itself: the soldiers may look similar in military uniform and unified in patriotic duty, but upon closer inspection, they are each a different, complex individual with varying emotions, memories, values and aspirations.

But in the context of war, these men – individuals as they may be – are bound by a similar kind of despair, nihilism and loss of faith. We see this reinforced by the use of the refrains.

If we juxtapose the final lines of each stanza, we’ll see a pattern emerge as such:

But nothing happens.

What are we doing here?

But nothing happens.

But nothing happens.

Is it that we are dying?

We turn back to our dying.

For love of God seems dying.

But nothing happens.

Technically, there’s only one perfect refrain in this poem, and that’s the statement – “But nothing happens”, which we find at the end of stanzas 1, 3, 4, and 8.

The fact that we begin and end with this pronouncement suggests the triumph of apathy, and highlights the grim reality of there being no messianic force or deus ex machina to deliver these soldiers out of their suffering.

As much as we’d like there to be a change in fortune for the better, Owen’s view is that such deliverance doesn’t really exist, which echoes the crisis of faith that so troubles the speaker in this poem.

And we see this reflected in the other thread of refrains, from ‘Is it that we are dying?’, to “We turn back to our dying”, to “For love of God seems dying”.

The refrain of “dying” shows the all-encompassing breakdown of the speaker (and his fellow sentries), as their ‘dying’ isn’t just the existential sort,, but extends also to their philosophical, spiritual and religious consciousness.

So it’s telling, then, that when we reach the final stanza, regularity is restored to some extent, as the lines alternate between iambic and trochaic hexameters, with lines 36-39 ending on a masculine stress (courtesy of the docked syllable, which also makes lines 37 and 39 catalectic), before it reverts to the feminine ending of the refrain “But nothing happens” (again, because of the final docked syllable).

The suggestion of this is pessimistic: despite the speaker’s desire and will to retain his individuality, the oppressive force of war is just too overpowering for this to be possible.

The syntax in the penultimate stanza (7) deserves some attention, especially that of lines 33-35 –

“For God’s invincible spring our love is made afraid;

Therefore, not loath, we lie out here; therefore were born,

For love of God seems dying.”

But first, what is the speaker saying here? The word “loath” means “unwilling”, and yet here Owen uses a double negative “not loath” to express the soldiers’ ‘not-unwillingness’ to be out in the fields. But does this mean that they are actually willing?

The wordplay could offer a clue: “loath” could remind us of “loathe” with an ‘e’, which means hatred, and this perhaps points us towards the men’s true emotions about their situation.

Are they lying out here in the battlefield because of “love” for country and God, or rather, a “love [that’s] made afraid”, which ceases to be a feeling of love, but terror?

The twisted, dislodged phrases, chopped up by caesurae in a way that mirrors the men’s emotional and mental fragmentation, convey the inner writhing that the speaker feels about the whole business of war.

The use of “therefore” supposedly connotes causality, but the irony is that everything has now become so illogical, the brutality of war so inexplicable, that the order between life and death, like the order of the clauses, has become reversed, and the reason for fighting is tangled up in the confusion and fusion of love and fear.

An intertextual tangent…

We can compare this syntactical jumble to another poem about loss of faith – Gerard Manley Hopkins’ ‘Carrion Comfort’ (1885), which opens like this:

Not, I’ll not, carrion comfort, Despair, not feast on thee;

Not untwist – slack they may be – these last strands of man

In me or, most weary, cry I can no more. I can;

Can something, hope, wish day come, not choose not to be.

Like the speaker in ‘Exposure’, Hopkins’ speaker is also struggling with thoughts of despair, as he feels his faith, humanity and verbal logic slipping away. Notice that the lines here are similarly jumbled and disorderly, with the shared word “not” indicating a sense of emotional resistance.

Interestingly, Hopkins also uses a hexameter structure in this poem. It’s worth noting that English verse doesn’t lend itself very naturally to anything longer than the pentameter.

So perhaps when poets like Owen and Hopkins decide to adopt the hexameter, they are precisely exploiting the awkward, prodding nature of the six-foot line to convey discomfort and disarray – despite a need to carry on.

Before we move on to ‘Bayonet Charge’, I’ll make a final point about personification in this poem, which recurs throughout to bring out another irony about the soldiers’ situation. For an environment that is so deadly “silent”, nature and its agents seem remarkably alive, as we can tell from these descriptions:

“… in the merciless iced east winds that knive us”

“low drooping flares confuse our memory of the salient”

“… mad gusts tugging on the wire”

“Dawn massing in the east her melancholy army

Attacks once more in ranks on shivering ranks of grey”“the air that shudders black with snow”

“…sidelong flowing flakes that flock, pause, and renew,

We watch them wandering up and down the wind’s nonchalance”“Pale flakes with fingering stealth come feeling for our faces”

“For hours the innocent mice rejoice: the house is theirs;”

“Since we believe not otherwise can kind fires burn;

Now ever suns smile true on child, or field, or fruit”“this frost will fasten on this mud and us,

Shrivelling many hands, and puckering foreheads crisp.”

While the humans are hanging by a thread, nature is flourishing in her apathy and inflicting pain on man.

It’s certainly strange to see that the brutality at play doesn’t really come from the usual accoutrements of war; the only presence of weaponry we see is in line 16, “Sudden successive flights of bullets streak the silence”, but ironically, the bullets are “less deadly than the air that shudders black with snow”.

Bullets, a human invention, are apparently less powerful than the bare cold wind, which highlights both the harsh conditions of the landscape, and the relative inferiority of man versus nature.

After all, Nature herself is immune from the bullets and ammunition that men themselves so fear.

What’s most tragic, though, is that while “merciless… winds” hurt, the “kind fires” of the “suns” which “smile true on child, or field, or fruit” cannot heal – not the wounded body, nor the disillusioned soul.

As such, Owen uses personification to show the men – the ‘persons’ at war – in their least person-like state, as they are reduced by nature’s force and man’s own inhumanity.

Watch the video on this:

Reading Ted Hughes’ ‘Bayonet Charge’ (1957): sharp edges and endless circles

Whereas the speaker of ‘Exposure’ comes out his stupor in muted drowsiness, the one in ‘Bayonet Charge’ wakes up from the trigger of a violent spurt.

The dactyl “Suddenly” plunges the reader right into the heart of the action, as the poem’s narrative opens in medias res.

Thereafter, it’s speed, noise, sound and fury all rolled into one, as we see the soldier running and stumbling his way across a field.

The language is chock full of kinaesthetic imagery, but as we reach the second stanza, there is a temptation for all the “running”, “stumbling”, “smacking”, and “sweating” to stop altogether, as the speaker asks himself the million dollar question of why.

Why is he running; what is he running from; and what is he running towards?

If we pay attention to the shape of the stanzas, we’ll notice that there’s one protruding line that juts out in each stanza, which offers a visual mimicry of the bayonet at the tip of a rifle, but also a formal re-enactment of the speaker’s forward-lunging momentum. In particular, lines 3 and 19 –

“Stumbling across a field of clods towards a green hedge”

And

“He plunged past with his bayonet toward the green hedge”

-marry the hypercatalectic lines with the image of the speaker running and plunging forward.

But the symbolism of the “green hedge” rubs against what’s happening in the poem. Hedgerows are normally found in well-maintained, orderly gardens, while greenery connotes life.

The speaker, however, is clearly in a state of disorder, and the danger that surrounds him positions him closer to the axis of death.

Is he, then, running towards a vision of hope, despite its seeming unreachability, which is implied by the fact that he begins running towards the hedge, and continues running towards this same hedge even as the poem reaches its end?

This question of just what the speaker is running for is examined in the middle stanza, which also happens to be one line shorter (a septet) than the first and final stanzas (both octets).

At this point, the bifurcation of outward and inward action comes to the fore: the soldier doesn’t stop running (“he almost stopped”), but his mind suspends for a moment to consider, “in bewilderment”, the forces that compel and propel him to keep running.

In what cold clockwork of the stars and the nations

Was he the hand pointing that second? […]

Here, Hughes combines the metaphor of “clockwork” with the metonymy of “the stars and the nations”.

These lines zoom out from the scrutinising, microscopic glare that has so far been posed on the speaker in the first stanza, and lead us to question just how the soldier came to be in the very moment, situation and role he finds himself in.

The metaphor of the clockface and the soldier as the clock “hand” conveys a sense that the man is running out of time (and so must run even faster), but also functions as a memento mori – the idea that no matter how quickly or desperately he runs, he is (and we are) only ever running towards death.

In this light, the idea of moving “toward the green hedge” reads like a sad mockery of man’s desire to cling onto life, especially when the reason for living isn’t always entirely clear – or even desirable.

Meanwhile, “the stars” and “the nations” are metonymic substitutes of fate and politicians – forces which, to varying extents, appear to ultimately dictate how everyone’s lives turn out.

And so, these ‘forces’ prod the soldier onwards in a blind frenzy of compulsive movement, which the enjambment from line 11 to the first half of line 14 cinematically reflects –

He was running

Like a man who has jumped up in the dark and runs

Listening between his footfalls for the reason

Of his still running,

The phrase “still running”, however, jolts us out of this kinaesthetic stream, as it hits against the caesura of the comma, and proceeds into the static suspension of –

and his foot hung like

Statuary in mid-stride.

There’s two ways of understanding “still running”, depending on whether we read the word “still” as an adjective or an adverb. As an adverb, “still” means ‘continue in the same way’, which aligns with the literal action of the soldier in this scene.

As an adjective, though, “still” means ‘not moving’ or ‘deep silence’, in which case the phrase becomes an oxymoron, and crystallises the asynchronous chasm between outer movement and inner thought – his limbs are moving, but his mind has already come to a standstill.

The sense here is that something’s amiss, whether it be the reason for his constant, frantic footfall, or the rationale behind being a part of this madness of war, or even – the missing eighth line from this septet, mirrored also by the incompleteness of the “mid-stride”.

There are a lot of similes in this poem, but what makes them interesting is the way they form a collective image of circularity. Note the circular motif in the objects and actions of this poem:

– The cyclical shape one’s legs make when running

– Reference to “bullet smacking the belly out of the air”

– “The patriotic tear that had brimmed in his eye

– Sweating like molten iron from the centre of his chest”

– The metaphor of the clock

– The “yellow hare that rolled like a flame

– And crawled in a threshing circle”

– Its “mouth wide/Open silent, its eyes standing out”

And what of this circularity?

Perhaps Hughes is suggesting that there is no end to the business of warfare, and that even if one manages to outrun a bullet, there are greater forces (recall “the stars and the nations”) that keep the cycle of war going; that even if one battle concludes, another one will emerge in due course.

The anatomical ‘circles’ of legs running, an open-wide mouth and teary or bulging eyes are juxtaposed against the ‘circles’ of temporality (“cold clockwork”) and hellishness (“rolled like a flame”), which puts forth the simple, but pessimistic, idea that man can neither outrun time nor overtake his own potential for evil.

Finally –

King, honour, human dignity, etcetera

Dropped like luxuries in a yelling alarm

The cavalier touch of “etcetera” conveys that in times of war, the values that one is taught to hold dear – patriotism (“King”), decency (“honour”), “human dignity” – immediately lose their importance, and if pursued, could even jeopardise one’s chances of survival.

As such, there is a need to jettison them as one would bombs, which is why they are here “dropped like luxuries in a yelling alarm”.

By comparing these values to “luxuries”, Hughes mocks the naivete of those who claim that war is fought for noble causes, because one is almost always forced to dispense with nobility in the heat of battle, and to prize survival above all else.

Watch the video on this:

To read my analysis of other poems, check out my posts below:

- An analysis of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘Love’s Philosophy’ and Lord Byron’s ‘When We Two Parted’ (Romantic poetry)

- An analysis of William Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’ and John Keats’ ‘To Autumn’ (Romantic poetry)

- An analysis of John Agard’s ‘Checking Out Me History’ and Maya Angelou’s ‘Still I Rise’ (BAME poetry)

- An analysis of Robert Browning’s ‘Porphyria’s Lover’ and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s ‘Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’ (Dramatic monologue)