One of my favourite words in English is ‘misnomer’, which means an inaccurate name for something.

An example is ‘fish pie’, which isn’t really a ‘pie’ in the traditional sense of the word (there’s no pastry crust), and the filling often includes other types of seafood additional to fish.

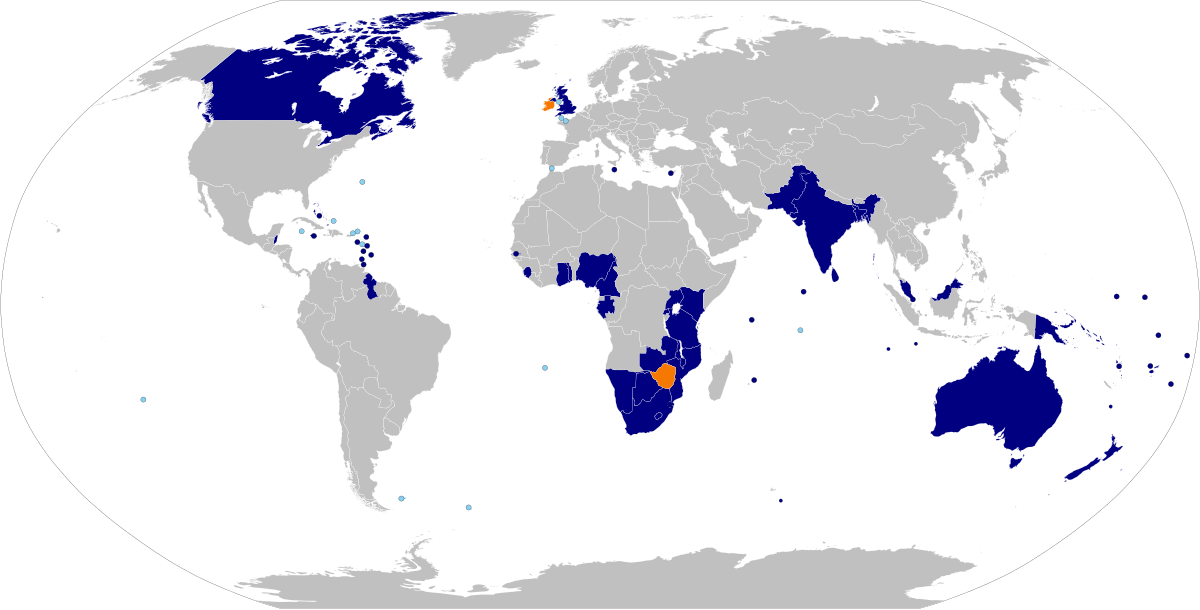

Another one would be ‘the Commonwealth of Nations’, which is a geopolitical association of 54 sovereign states formerly under British rule. Given that this group includes countries with vastly different GDP/GDP per capita levels (e.g. Ghana and Canada), the term ‘commonwealth’ can hardly be taken literally.

In poetry analysis, an important misnomer is ‘blank verse’, which has always been a favourite among the ‘Great’ English poets. Much of Shakespeare’s plays were written in blank verse; Milton’s epic Paradise Lost is also in blank verse; Tennyson, Browning, Wordsworth et al were all fans of blank verse. But there’s nothing ‘blank’ – as in empty or boring – about blank verse, which is why the term itself doesn’t do much to help us understand what it is.

What is blank verse, and why were the ‘Greats’ all over it?

The most straightforward definition of ‘blank verse’ is unrhymed iambic pentameter.

More specifically, it is a poetic form which does not follow a rhyme scheme, but adopts a set meter (usually iambic pentameter). According to the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics –

Blank verse is a term for unrhymed lines of poetry, always in lines of a length considered appropriate to serious topics and often in the most elevated, canonical meter in a given national prosody.

In English prosody, this “most elevated, canonical meter” is none other than iambic pentameter, which has been the go-to meter for such “serious topics” as the relationship between man and God (Paradise Lost), the follies of overreaching ambition (Macbeth), the connection between humanity and nature (The Prelude) etc.

What lends blank verse its dignified stature is two-fold: on the one hand, it isn’t subject to rigid constraints of sonic regularity; equally, it retains a measure of steadiness in flow which makes it an appropriate vehicle for notions of stateliness and solemnity.

While ‘blank’ verse doesn’t have much to do with blankness, ‘free verse’ is closer to what it purports to be – it refers to verse that’s free from all prosodic prescriptions.

While blank verse is unrhymed but metrical, free verse is unrhymed and unmetrical, which makes it the closest verse form to prose. The line between free verse and prose, while thin, is defined, and is usually determined by the presence of lineation (so spoken free verse may be a bit harder to distinguish from a prose passage).

A whistle-stop tour of the history of blank verse

Unlike blank verse, which has a longer, more illustrious history dating back to the Italian and English Renaissance, free verse is a considerably more modern form. At the very least, it didn’t gain traction as an actual prosodic type until the late 19th century, when the French Symbolists began to use vers libre as an approach to stylistic experimentation.

The Anglosphere soon caught on, and come early 20th century, the Modernists made free verse the ‘new cool’ and attributed all sorts of ideological virtues to shunning rhyme and meter. While there were those in the avant-garde camp who initiated a wholesale rejection of prosodic form, other Modernist poets like T. S. Eliot and D. H. Lawrence were more reserved in their attitude towards a poetics entirely removed from tradition and structure.

As Eliot writes in his essay ‘Reflections on vers libre’, by advocating free verse, poets aren’t necessarily lodging “a campaign against rhyme”, but making the first step to modernizing poetry by breaking away from rigid schemes and conventions –

“… ‘Blank verse’ is the only accepted rhymeless verse in English – the inevitable iambic pentameter. The English ear is (or was) more sensitive to the music of the verse and less dependent upon the recurrence of identical sounds in this metre than in any other. There is no campaign against rhyme. But it is possible that excessive devotion to rhyme has thickened the modern ear. The rejection of rhyme is not a leap at facility; on the contrary, it imposes a much severer strain upon the language. When the comforting echo of rhyme is removed, success or failure in the choice of words, in the sentence structure, in the order, is at once more apparent. Rhyme removed, the poet is at once held up to the standards of prose. Rhyme removed, much ethereal music leaps up from the word, music which has hitherto chirped unnoticed in the expanse of prose…”

Broadly speaking, then, the popularity of the blank verse picked up steam with Shakespeare and Milton’s endorsements, only to wane at the cusp of the 20th century, when formal and stylistic experimentation became the literary mission du jour. Post-WWII, though, we’ve seen both blank and free verse adopted by poets across the board, which should attest to the timeliness and flexibility of these forms.

Seeing as I’ve already written about the blank verse of British writers like Shakespeare, Milton, Browning and Wordsworth, as well as the free verse of T. S. Eliot (albeit always with a different or wider emphasis), I figured that in this post, we could look at Irish and American poets instead – W. B. Yeats and Marianne Moore.

…Did you know that I also have a YouTube channel with lots of useful English Lit videos? Check it out and subscribe for more useful content!

Reading the blank verse of W. B. Yeats’ ‘The Second Coming’: “the centre cannot hold”

Today, Yeats is largely known as a poet, but he was in fact a man of many personas.

He was a lifelong Irish nationalist, a theatre owner, an ardent playwright, a fervent occultist, a Nobel Prize winner – and above all, a great poet.

Part of his appeal lies in the diverse, and often, conflicting, facets of his character, but the chasms he embodied make him the fascinating, transitional figure that he is. Yeats was also a man of contradictions: he saw himself as Irish to the last, but had lived in London for more than 40 years; he was influenced by modernist Poundian aesthetics in drama, but had rejected much of the stylistic ‘glass-breaking’ championed by Pound (and to a lesser extent, Eliot) in his poetry; he believed in mystical, occultist ideas that had little basis in science or reality, and yet he often reached for real humans and material things as the main subject of his works.

As someone who had lived through a concatenation of crises – from World War I (1914-1919), the Spanish Flu (1918-1920), the Ango-Irish War (1919-1921), then the Irish Civil War (1922-1923) and the social collapse that came with it all, Yeats nonetheless held fast to a sense of optimism, which is reflected (I think) in his famous poem ‘The Second Coming’.

According to Factiva, ‘The Second Coming’ was the most quoted poem in 2016, a year when populism and terrorism reared their ugly heads in worrying ways, from Trump’s election to Brexit to the bombings in Iraq, Syria, Brussels etc. It’s also a poem that has long made its way into the cultural allusive fabric, with Chinua Achebe’s 1958 postcolonial novel Things Fall Apart and Joan Didion’s 1968 essay collection Slouching towards Bethlehem being famous examples.

The irony, however, is that most people tend to just quote the first stanza of Yeats’ poem – the pessimistic part, without noticing that the second stanza offers – for all its dark imagery – a glimmer of hope. Granted, this ‘hope’ isn’t of the cheeriest variety, as Yeats’ idea is that there will be redemption after an apocalypse – but the apocalypse must first arrive for the slate to be wiped clean again for rebirth.

This distinction between apocalyptic grimness in the first stanza and post-apocalyptic anticipation in the second stanza is largely reinforced by Yeats’ use of blank verse. While the first stanza is completely in blank verse, the rest of the poem diverges from this form at points.

The first stanza in ‘The Second Coming’ (lines 1-7)

In the first stanza, note that each line contains 10 syllables –

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

The reference to “the widening gyre” needs a bit of explaining here: Yeats believed that history followed certain patterns created by the constant interplay of micro actions and macro conditions, and one of these patterns was the “gyre” – a spiralling vortex. All historical events take place in this “gyre”, which contains a gravitational force that is supposed to hold things together.

And yet, placed at the crossroads of large-scale war and mass human suffering, Yeats saw the dawn of the 20th century as a sign of total disintegration, which is why the “gyre” is “widening” in its defiance of unity, leading to what is probably the most oft-quoted line in this poem – “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold”.

The tension between content and form is obvious here: what’s described is a world in bedlam, but the disarray is framed within the structural integrity of blank verse, as it turns out one iambic unit after another in a five-by-five pentameter sequence (although a case could be made for the first line being a combination of dactylic and anapestic units, as in –

TUR-ning and TUR-ning in the WI-de-ning GYRE;

(\ u u \ u u u \ u u \)

… which sets us up with the expectation of change and collapse, despite the semblance of metrical stability that resumes for the rest of stanza 1 (from lines 2-7).

This suggests, then, the speaker’s desire to hold the unholdable, and that despite the arrival of an engulfing, tragic force – as evident in the imagery of flooding in “mere anarchy… loosed upon the world/The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere/The ceremony of innocence is drowned”, it is necessary to project a sense of composure, even if such composure comes in little more than a hollowed-out shell.

In the face of chaos unleashed, misplaced ‘convictions’ and extreme passions, maintaining a dignified front is perhaps the one last stand against complete destruction.

The second stanza in ‘The Second Coming’ (lines 8-21)

With the pivot into the second stanza, the speaker alludes to “the Second Coming”. In the premillennialist eschatology, Christ returns to the Earth before the Millennium, which is a literal thousand-year peace age as prophesied in the Book of Revelation. But there’s a sarcastic edge to this allusion, which the emphatic adverb “surely” gives away –

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming!

Throughout history, we’ve seen many prophets declare the imminence of such ‘Second Comings’, but so far, none has materialised. This impulse to hold out on the false hope of deliverance is then debunked by “a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi” which “troubles my [the speaker’s] sight” –

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out (one extra syllable – hypercatalectic)

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi (two extra syllables – hexameter)

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert (three extra syllables – hypercatalectic hexameter)

A shape with lion body and the head of a man, (three extra syllables)

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it (one extra syllable – hypercatalectic)

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds. (one extra syllable – hypercatalectic)

The darkness drops again;

With the rise of this sphinx-like figure, the speaker realises that the ‘Second Coming’ he’s witnessing brings neither redemption nor relief.

Instead, with its “gaze blank and pitiless”, it attracts more signs of gloom, more reminders of death – those “shadows”, desert vultures, and the “darkness” that descends.

Notice, too, that this section in the poem departs from the stately blank verse tempo we’ve seen in the first stanza, when the lid remains, as it were, placed on the pressure cooker of pandemonium. It’s certainly interesting that lines 11, 12 and 13 contain 11, 12 and 13 syllables respectively (contra the 10 syllables of the blank verse).

And this metrical accumulation peaks at the point of the sphinx’s full display. In Greek myth, the sphinx is known for her riddle of “which creature has one voice, and becomes four-footed, two-footed then three-footed?” The answer, of course, is man, and in the context of this poem, the implication may be that any hope of deliverance lies first in the human world, but time and again, we see man letting itself down with cycles of brutality, violence and mutual destruction.

So, the metrical divergence perhaps highlights the emotional intensity that the speaker feels upon being met with this overwhelming vision; equally, it may be a looking-forward to the arrival of a once-in-a-century, anomalous year that concludes one historical dispensation and heralds the beginning of another.

Reading the free verse of Marianne Moore’s ‘Poetry’: “we do not admire what we cannot understand”

Before we move onto Marianne Moore’s meticulous free verse, I’d like to share two other Modernist examples to highlight just how pliable ‘free verse’ can be as a prosodic category:

As she laughed I was aware of becoming involved in her laughter and being part of it, until her teeth were only accidental stars with a talent for squad-drill. I was drawn in by short gasps, inhaled at each momentary recovery, lost finally in the dark caverns of her throat, bruised by the ripple of unseen muscles. An elderly waiter with trembling hands was hurriedly spreading a pink and white checked cloth over the rusty green iron table, saying: “If the lady and gentleman wish to take their tea in the garden, if the lady and gentleman wish to take their tea in the garden …” I decided that if the shaking of her breasts could be stopped, some of the fragments of the afternoon might be collected, and I concentrated my attention with careful subtlety to this end.

· ‘Hysteria’, T. S. Eliot

Green arsenic smeared on an egg-white cloth,

Crushed strawberries! Come, let us feast our eyes.· ‘L’art, 1910’, Ezra Pound

To most people, neither poem reflects a conventional understanding of ‘poetry’ – free verse or otherwise. Eliot’s ‘Hysteria’ might as well be a prose excerpt, and Pound’s ‘L’art’ seems more like a momentary exclamation than an actual poem. But that, of course, is the whole point of free verse’s Modernist renaissance – these poets leveraged the ‘freedom’ of ‘free verse’ to make an ideological statement about the boundaries of literary art, namely that there should be little to no boundaries at all.

And yet, when poetry becomes absent of all poetic value, it’s perhaps fair to question whether such poetry deserves its title, or if it fundamentally ceases to be what it claims to be. If the value of a poem lies in its being a reservoir of human experience conveyed through artistic form, then any attempts at ‘formal experimentation’ should also be done in service of humanity, not politics.

This, at least, appears to be the message of Moore’s aptly titled poem ‘Poetry’, which reads more like a pamphlet than a poem, but shows through its skilfully wrought form the possibility of marrying free verse with aesthetic integrity.

The speaker opens by acknowledging, with no less than a sheepish, self-reflexive wink, that “I, too, dislike it: there are things that are important/beyond all this fiddle.”, with the “it” here referring to the much ado of writing poetry (especially in the Modernist milieu that Moore herself was part of). The sort of densely allusive free verse that Eliot, Pound et al tended to write seems embarrassing to Moore’s speaker, who “reading it… with a perfect contempt”, sees poetics for its real value – it is “a place for the genuine”, a written compendium of human actions, feelings, sensations recorded for all time, for all people. In verse, there should be –

Hands that can grasp, eyes

That can dilate, hair that can rise

If it must, these things are important not be-

Cause a

High sounding interpretation can be put upon them

But because they are

Useful; when they become so derivative as to

become unintelligible, the

Same thing may be said for all of us – that we

Do not admire what

We cannot understand.

There’s a dig at literary critics couched within there, too, when the speaker refers to the “high sounding interpretation” that’s often enabled and encouraged by both ‘difficult’ writers and English professors. As James Joyce once said, his notoriously challenging novel Finnegans Wake (because it is largely unintelligible, densely inventive and thickly allusive) is sure to keep English academics in business for at least the next century. Moore, however, seems to care about the idea of poetry (and literature, by extension) being “useful”, which doesn’t necessarily mean it has to be instructive or didactic, but more documentative and demotic – both reflective of and accessible to the human psyche.

One of the most interesting features of this poem is that despite its layman register, its form is elaborately architected – almost in a mocking way. We are forced to question if there’s anything at all to the ways the lines taper and cascade in varying lengths, and to stop short of ‘falling into Moore’s trap’, as it were, when we suspect that we may be missing the wood for the trees by focusing too much on the form at the expense of the argument.

This tension reveals the beauty and danger of free verse: it’s a groundbreaking prosodic form because it has expanded the scope of poetic concerns, but on the other hand, it offers the temptation of excessive tampering and frivolous reading, to the extent where perhaps some poets are content to cobble together whatever materials and call the motley a ‘free verse’ poem –

The bat,

holding on upside down or in quest of some-

thing to

Eat, elephants pushing, a wild horse taking a roll,

a tireless wolf under

a tree, the immovable critic twinkling his skin like a

horse that feels a flea, the base-

ball fan, the statistician – case after case

Could be cited did

One wish it; nor is it valid

To discriminate against “business documents

and

School-books”; all these phenomena are important.

This is a periodic sentence dragged out through a ragtag of pedestrian observations, implied uninspired characters like “the immovable critic… the baseball fan, the statistician” and the Tolstoyan disdain for “business documents and school-books”, only to end on the concession that “all these phenomena are important”. But while they bear significance in their respective contexts, whether or not they belong to the sacred realm of poetic imagination is an entirely different discussion (and the speaker’s view is no).

As the poem reaches its conclusion, we hear Moore’s own philosophy of poetics declaring itself through firm – at times scathing – words carried across winding lines –

One must make a distinction

however: when dragged into prominence by half

poets,

the result is not poetry,

nor till the autocrats among us can be

“literalists of

the imagination” – above

Insolence and triviality and can present

For inspection, imaginary gardens with real toads

in them, shall we have

It.

This is a clear point delivered in circumlocutory syntax, but the point is, of course, that these “half/poets” – cheekily ‘severed’ by dint of Moore’s line break – “drag into prominence” things which have no place in verse. The ‘freedom’ of ‘free verse’ isn’t a free-for-all, and just because someone combines a random item or document with another random item or document doesn’t make it revolutionary or ‘experimental’ poetry. There is a need, then, for the hoity-toity Modernist ideologues and aesthetes (“the autocrats among us”) to recalibrate their view on the balance between content and form, and – contra Yeats – become “literalists of/The imagination”, go back to basics and present in their works what is evident to their creative minds.

There is tremendous ripeness in reality for poetic production, and for all the ‘revolutionary’ zeal that the Modernist pivot from more traditional prosodic forms (like blank verse) to free verse, Moore seems to believe that it is “the raw material of poetry in/all its rawness” which gives poems their “genuine”, authentic voice. And so the poem ends on a clarion call that is probably no less ideological than the views of the ideologues she attacks –

In the meantime, if you demand on one hand,

In defiance of their opinion –

The raw material of poetry in

All its rawness, and

that which is on the other hand,

Genuine, then you are interested in poetry.

The greatest irony, then, is that for Moore, while free verse has enabled the birth of pseudo-poets – it has also exposed the difference between the pseudos and the real, authentic champions of poetry.

To read my analysis of other poems, check out my posts below:

- What is an ode? Reading Keats’ ‘Ode on Melancholy’ to find out

- Guilt in poetry: Reading Robert Browning’s ‘My Last Duchess’ and William Wordsworth’s ‘Extract from The Prelude’

- Freedom in poetry: Reading Sylvia Plath’s ‘Pheasant’ and Ted Hughes’ ‘Hawk Roosting’

- Comparing love poetry (II): Reading Philip Larkin’s ‘Wild Oats’ and Carol Ann Duffy’s ‘Valentine’