Note: this post contains spoilers!

What is the mark of a truly successful writer?

Is it when most people have read your work, or when most people have heard of you before they have even read your work?

Or, is it when your name enters common parlance as an adjective, as in the case of the word ‘Orwellian’?

It’s surely one of the finer ironies in English Literature that George Orwell, lifelong democratic socialist that he was, should have his posthumous reputation so closely tied to an ideology that he had spent most of his life critiquing.

After all, to describe a situation as ‘Orwellian’ is to say that it’s totalitarian and tyrannical, much like the fictional superstate of Oceania in his famous novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (which was published in 1949).

Modelled on Stalinist and Fascist nations in the early 20th century, Oceania is a surveillance state, socio-political nightmare, and dystopian frankenstein.

I’ve written about two other dystopian novels before – Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). Both works present vivid, brilliant speculations of what a ‘world gone wrong’ could look like, but neither comes close to Orwell’s vision in terms of its veracity and approximation for the current times.

Totalitarianism, authoritarianism and fascism – what’s the difference?

Whenever people speak of dictatorships, the triptych of ‘totalitarianism’, ‘authoritarianism’ and ‘fascism’ always crops up. But just how similar or different are these three terms?

According to the dictionary –

Totalitarianism: a government with almost complete control over the lives of its citizens and does not permit political opposition

Authoritarianism: a belief that people must obey completely and not be allowed the freedom to act as they wish

Fascism: a political system based on a very powerful leader, state control, extreme national and racial pride, in which political opposition is not allowed

As the definitions show, while ‘authoritarianism’ is an ideology, ‘totalitarianism’ is a mode of governance which emphasises absolute control over its people. ‘Fascism’ is similar, but it carries a nationalistic connotation which is absent from totalitarianism.

What is Nineteen Eighty-Four about?

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, ‘Big Brother’, the numinous figurehead of the Ingsoc Party whom everyone obeys and venerates (or is supposed to), is the totalitarian presence which looms large over all aspects of social and individual life.

Despite being a Party member, the protagonist Winston Smith finds himself at odds with the ideological values imposed on him. Blind obedience, willing slavishness, unthinking loyalty, and obsessive self-censorship – these are the necessary qualities of Party members, and the very qualities that Winston abhors.

Unfortunately for Winston, he realises early on that he’s dangerously ‘unorthodox’ as someone who neither believes in nor worships Big Brother.

From the Party’s vantage, then, he is an ‘enemy of the people’.

One of the key motifs in this novel is a desire for the past and for memory. Ironically, while Winston constantly tries to recall past events from the pre-Big Brother era, he works at the Records Department as a ‘rewriter’ of history.

As part of the state’s revisionist machine, Winston’s job is to ensure that whatever happens at present matches up with whatever Big Brother had ‘already’ said.

The undisputed truth is, of course, that Big Brother, and by extension, the Party, can never be wrong.

Winston is nostalgic for the past not because of any specific incident, but because he craves the feeling of being human – with its messy capacity for love, doubt, passion, empathy, thought and nuance.

Living under the eyes of Big Brother, there is only room for fear, obedience, and hatred for ‘the enemy’ in a hyper-sterilised state.

The most unlikely love story… or is it?

In his search for human experience, Winston falls in love and begins a clandestine relationship with Julia, a fellow Party member who works at the Fiction Department and is active in the Junior Anti-Sex League (ironic, given how sexually liberated she is portrayed to be).

Beneath her pro-Party pretense, Julia, like Winston, doesn’t believe in any of the Party tenets, which makes the two characters ‘comrades in heretical arms’.

Unlike Winston, however, Julia’s rebellion is rooted in sensual, not intellectual, wants, as she cares more about satisfying the pleasures of the flesh than recovering the state of the past, the latter which is a central concern for Winston.

Still, both of them agree on one thing: the fact that they love each other is the greatest act of subversion against the totalitarian state, wherein love can only be reserved for Big Brother alone.

Conscious that their relationship is doomed, Winston says to Julia in one of their intimate moments –

“We may be together for another six months – a year – there’s no knowing. At the end we’re certain to be apart. Do you realise how utterly alone we shall be? When once they get hold of us there will be nothing, literally nothing, that either of us can do for the other. If I confess they’ll shoot you, and if I refuse to confess, they’ll shoot you just the same. Nothing that I can do or say, or stop myself from saying, will put off your death for as much as five minutes. Neither of us will even know whether the other is alive or dead. We shall be utterly without power of any kind. The one thing that matters is that we shouldn’t betray one another, although even that can’t make the slightest difference.”

“If you mean confessing,” [Julia] said, “we shall do that, right enough. Everybody always confesses. You can’t help it. They torture you.”

“I don’t mean confessing. Confession is not betrayal. What you say or do doesn’t matter; only feelings matter. If they could make me stop loving you – that would be the real betrayal.”

(Part 2, Ch. 7)

But in a totalitarian state, what does ‘love’ really mean?

Unlikely as this question may seem for a book such as Nineteen Eighty-Four, it is actually the single most important issue Orwell poses in the book.

In a Christian and humanistic sense, love means extreme sacrifice – the willingness to suffer at the expense of another; in the totalitarian sense, love means absolute obedience.

Unlike sacrifice, obedience doesn’t require individual agency – one cannot choose to love Big Brother. One’s love for him must be instinctual, second nature, a sort of natural desire one can’t imagine living without.

Nineteen Eighty-Four, in many ways, always circles back to this fundamental tension between ‘love as sacrifice’ and ‘love as obedience’.

But if the willingness to love and sacrifice is what makes one truly human, does Winston ultimately attain the humanity that he so yearns?

* * *

To find out, let’s close read one of the most important scenes in the book. It comes towards the end, when Winston is interrogated and tortured by O’Brien, a powerful Inner Party member who first wins Winston’s trust with cryptic words and looks, only to eventually reveal himself as a true Party believer and a sadistic torturer.

Love as subversion: “I have not betrayed Julia”

Upon seeing how emaciated and pathetic his skeletal body looks after a long period of being tortured by O’Brien, Winston breaks down in humiliation –

“You did it!” sobbed Winston. “You reduced me to this state.”

“No,” [said O’Brien], you reduced yourself to it. This is what you accepted when you set yourself up against the Party. It was all contained in that first act. Nothing has happened that you did not foresee.”

He paused, and then went on:

“We have beaten you, Winston. We have broken you up. You have seen what your body is like. Your mind is in the same state. I do not think there can be much pride left in you. You have been kicked and flogged and insulted, you have screamed with pain, you have rolled on the floor in your own blood and vomit. You have whimpered for mercy, you have betrayed everybody and everything. Can you think of a single degradation that has not happened to you?”

Winston had stopped weeping, though the tears were still oozing out of his eyes. He looked up at O’Brien.

“I have not betrayed Julia,” he said.

O’Brien looked down at him thoughtfully. “No,” he said, “no; that is perfectly true. You have not betrayed Julia.”

(Part 3, Ch. 4)

What’s striking about the language in this scene is Orwell’s overwhelming use of the second-person pronoun ‘you’.

Save for the tyrannical “we” of the Party, which has “beaten” and “broken” the man down to his most ignominious state, O’Brien points out that Winston has got no one to blame but himself, because for all the torture that the Party has inflicted upon him, he was the one who allowed himself to give in.

No one had forced the screams of pain, the whimpers for mercy, and most of all, the betrayals of everybody and everything out of Winston’s larynx – the sounds have come out of his body ‘of their own accord’ (a recurrent phrase in the book), with the command to do so issued by nothing less than his own mind.

It seems, then, that human beings aren’t as civilised, strong or upright a creature as we often fancy ourselves to be. Had we been so, perhaps Winston – through sheer power of his will – would not have cowered in the face of suffering, however painful the suffering was.

This echoes one of O’Brien’s earlier remarks, when he points out that Winston is “here because you have failed in humility, in self-discipline.”

In O’Brien (and the Party’s view), recognising the limitations of human nature is the ultimate act of love towards the Party, and a true sign of complete submission to the totalitarian state.

But Winston concurs – “I have not betrayed Julia”, he cries.

This reminds us of his words to Julia earlier in Part 2, Ch. 7, after their usual rendezvous in the hideout above Mr Carrington’s shop, when he points out that for all the Party’s absolute permeation of their lives, it cannot control their feelings. The love they share is the last bastion they hold against tyranny.

At this point in the torture, Winston may have confessed every detail about his illicit romance with Julia, but deep within, he has not stopped loving her.

For this, Winston can convince himself that he’s scored a victory against the Party, albeit only in spirit.

But it is a momentary victory, if it is that at all…

Love as inconvenience: “Do it to Julia! Not me! Julia!”

Had Orwell been a bit more forgiving and less pessimistic about human nature, perhaps Nineteen Eighty-Four would have ended here, with O’Brien’s concession of Winston’s enduring love.

But alas, the plot must go on.

One night, after the moment above takes place, Winston “fell into a strange, blissful reverie”, in which he dreams of reuniting with Julia among “elm trees” and “green pools”.

Shocked by his “overwhelming hallucination of her presence”, Winston cries out in his sleep – “Julia! Julia! Julia, my love! Julia!”

He awakes to the terrifying awareness of having implicated himself, for if there’s anything O’Brien cannot condone, it is the ‘impurity’ of Winston’s love, which must be reserved for Big Brother alone – not Julia, and certainly not any memory of the past.

As a result, Winston is led to the final stage of his torture, which brings us to the horrific incident in Room 101…

“You asked me once,” said O’Brien, “what was in Room 101. I told you that you knew the answer already. Everyone knows it. The thing that is in Room 101 is the worst thing in the world.”

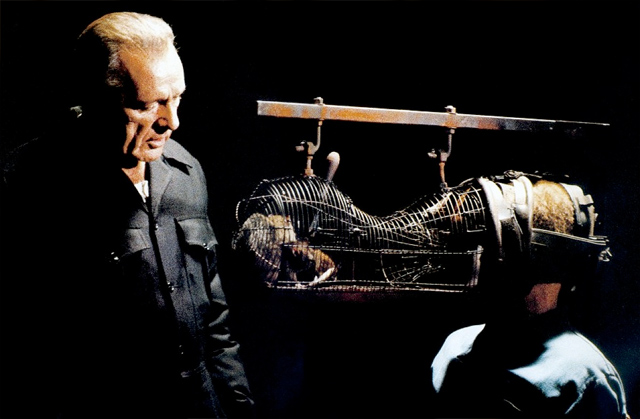

The door opened again. A guard came in, carrying something made of wire, a box or basket of some kind. He set it down on the further table. Because of the position in which O’Brien was standing, Winston could not see what the thing was.

“The worst thing in the world,” said O’Brien, “varies from individual to individual. It may be buried alive, or death by fire, or by drowning, or by impalement, or fifty other deaths. There are cases where it is some quite trivial thing, not even fatal.”

He had moved a little to one side, so that Winston had a better view of the thing on the table. It was an oblong wire cage with a handle on top for carrying it by. Fixed to the front of it was something that looked like a fencing mask, with the concave side outwards. Although it was three or four meters away from him, he could see that the cage was divided lengthways into two compartments, and that there was some kind of creature in each.

They were rats.

“In your case,” said O’Brien, “the worst thing in the world happens to be rats.”

A sort of premonitory tremor, a fear of he was no certain what, had passed through Winston as soon as he caught his first glimpse of the cage. But at this moment the meaning of the mask-like attachment in front of it suddenly sank into him. His bowels seemed to turn to water.

The “mask”, in addition to being the cover of the rat cage, also symbolises the veneer of human decency that every individual wears since birth.

In the Hobbesian worldview, traits such as love, civility, kindness and fellow feeling aren’t inherent to human nature, but are instead “mask-like attachment” that we affix onto ourselves by virtue of social conditioning.

In what circumstances, then, would such ‘attachments’ come off to reveal the primate that underlies the human?

To this, Orwell has an answer, but it’s not a promising one –

“You can’t do that!” Winston cried out in a high cracked voice. “You couldn’t, you couldn’t! It’s impossible.”

[…]

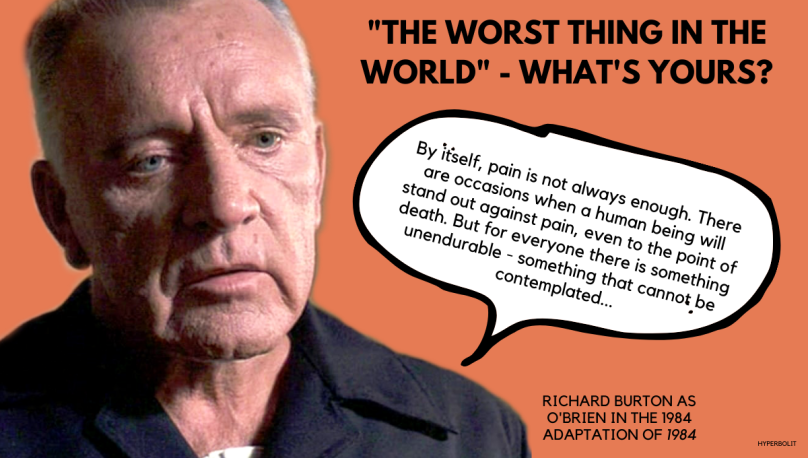

“By itself,” [O’Brien] said, “pain is not always enough. There are occasions when a human being will stand out against pain, even to the point of death. But for everyone there is something unendurable – something that cannot be contemplated. Courage and cowardice are not involved. If you are falling from a height it is not cowardly to clutch at a rope. If you have come up from deep water it is not cowardly to fill your lungs with air. It is merely an instinct which cannot be disobeyed. It is the same with the rats. For you, they are unendurable. They are a form of pressure that you cannot withstand, even if you wished to. You will do what is required of you.”

“But what is it, what is it? How can I do it if I don’t know what it is?”

O’Brien picked up the cage and brought it across to the nearer table. He set it down carefully on the baize cloth. Winston could hear the blood singing in his ears. He had the feeling of sitting in utter loneliness. He was in the middle of a great empty plain, a flat desert drenched with sunlight, across which all sounds came to him out of immense distances. Yet the cage with the rats was not two meters away from him. They were enormous rats. They were at the age when a rat’s muzzle grows blunt and fierce and his fur brown instead of gray.

[…]

There was an outburst of squeals from the cage. It seemed to reach Winston from far away. The rats were fighting; they were trying to get at each other through the partition. He heard also a deep groan of despair. That, too, seemed to come from outside himself.

O’Brien picked up the cage, and, as he did so, pressed something in it. There was a sharp click. Winston made a frantic effort to tear himself loose from the chair. It was hopeless: every part of him, even his head, was held immovably. O’Brien moved the cage nearer. It was less than a meter from Winston’s face.

“I have pressed the first lever,” said O’Brien. “You understand the construction of this cage. The mask will fit over your head, leaving no exit. When I press this other lever, the door of the cage will slide up. These starving brutes will shoot out of it like bullets. Have you ever seen a rat leap through the air? They will leap onto your face and bore straight into it. Sometimes they attack the eyes first. Sometimes they burrow through the cheeks and devour the tongue.”

The cage was nearer; it was closing in. […] The circle of the mask was large enough now to shut out the vision of anything else. The wire door was a couple of hand-spans from his face. The rats knew what was coming now. One of them was leaping up and down; the other, an old scaly grandfather of the sewers, stood up, with his pink hands against the bars, and fiercely snuffed the air. Winston could see the whiskers and the yellow teeth. Again the black panic took hold of him. He was blind, helpless, mindless.

[…]

The mask was closing on his face. The wire brushed his cheek. And then – no, it was not relief, only hope, a tiny fragment of hope. Too late, perhaps too late. But he had suddenly understood that in the whole world there was just one person to whom he could transfer his punishment – one body that he could thrust between himself and the rats. And he was shouting frantically, over and over.

“Do it to Julia! Do it to Julia! Not me! Julia! I don’t care what you do to her. Tear her face off, strip her to the bones. Not me! Julia! Not me!”

(Part 3, Ch. 5)

For all the thriller-esque nature of this torturous scene (and one can’t deny that Orwell is a master of narrative suspense), it is just as much a moment of intense tragedy.

Here, it is important that we recall an earlier instance in the novel – Part 2, Ch. 5, when Julia notices a couple of rats scuttling along the floorboard of their hideout, and Winston shudders in fear “with his eyes tightly shut”.

This is a key moment of foreboding, as we find out now that Winston eventually does ‘rat’ Julia out.

The main point, though, lies not in Winston’s emotional – and therefore complete – betrayal of Julia (which he has – till now – delusionally believed to be the one thing beyond the Party’s reach), but in the cold dish of brutal disillusionment that Orwell serves up, as we’re forced to acknowledge that in absolute desperation, we are utterly incapable of love and sacrifice.

Thrust in front of “the worst thing in the world”, self-protection is the first – and only thing – we reach for.

Nothing else apart from our own survival matters.

By selling Julia out, Winston shows that his ‘love’ for Julia does not exceed the love for himself.

And with this, he is truly defeated by O’Brien, as his response to the rat threat shows that the Party can get to both your mind and your heart, especially when it forces you to pick between avoiding and braving your worst fears.

At once, Winston’s final fortress against O’Brien’s dehumanisation crumbles, and he is ‘reborn’ from his re-education as a man unshackled from the burden and delusions of love. The most tragic thing about the way Nineteen Eighty-Four ends is perhaps the fact that Winston doesn’t die in the end.

To live with the memory of betrayal and the consciousness of broken humanity is arguably much, much worse than dying.

Reading Nineteen Eighty-Four raises a series of grim, but important, questions that we should all ask ourselves:

Do we really love our loved ones as much as we think we do?

Are we capable of sacrifice when the occasion asks for it, and if we don’t, does that make us less – or more – human?

And for all the moral decency and righteousness we believe ourselves to possess, do they come with a glaring footnote – one which caveats that when survival of the self is at stake, all bets are off?

Perhaps these are questions that we would only ever be forced to answer in a totalitarian state, and while we hope and pray such a day never arrives, these are nonetheless worth pondering over, even in hypothetical terms.

Indeed, it may even prove helpful for us to gain a sobering, humbling awareness of who we are and what we’re capable (and not so capable) of as humans.

For more key quotes from the novel, check out my Instagram post below: