Symbol, motif and theme – otherwise known as the triumvirate of literary fiction.

These three terms hold the key to unlocking the ‘deeper meaning’ of every literary work, but there’s a catch – they’re not always so easy to tell apart.

And when we confuse them for one another, we compromise the clarity and depth of our analysis.

In this post, then, I’ll be explaining the difference between symbol, motif and theme, and how we can differentiate between them. (Scroll down for a short animated explainer video!)

What is a ‘theme’ in literature?

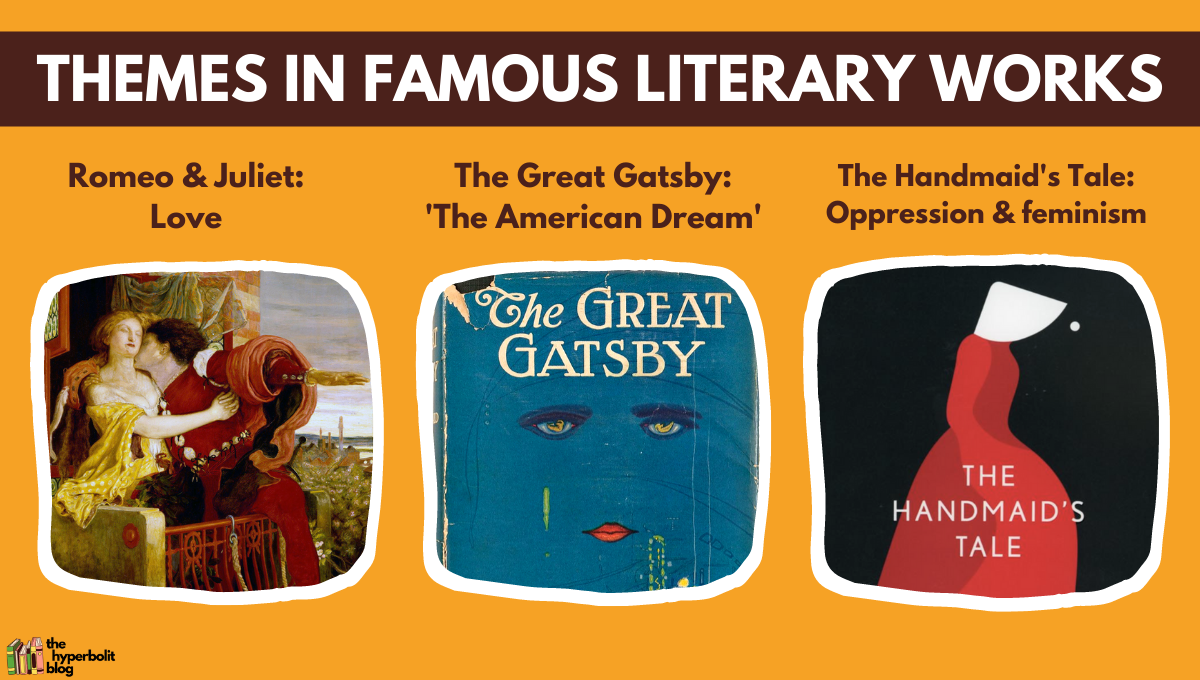

In literature, a ‘theme’ is simply the key subject matter of a text.

Broadly speaking, Romeo and Juliet is about love; The Great Gatsby is about ‘The American Dream’; The Handmaid’s Tale is about oppression and feminism etc etc.

The phrase “is about” signals a thematic concern, and themes are the cornerstone of literature – the bread and butter of creative inspiration.

After all, we could do without fancy narrative techniques and obscure allusive references, but a literary work that doesn’t contain at least one theme would be bland and uninteresting.

(unlike this lion cat / cat lion).

What is ‘symbol’, and what is ‘motif’?

Wait – are they not the same thing?

Or at least similar enough for us to not care?

Regarding the former, no, they aren’t.

As for the latter, I suppose you could, but that’s like not caring about the difference between simile and metaphor, personification and anthropomorphism, or paradox and oxymoron.

It’s not exactly the sort of thing most people lose sleep over, but it’s not such a great idea if you want to gain mastery in English Lit / are an English student and care about your grades.

Let’s start with first principles (i.e. dictionary definitions) –

Symbol: a sign, shape or object used to represent something else

Motif: an idea that is used many times in a piece of writing or music

Not bad, considering some of the other less clarifying definitions I’ve shown in other posts. For the definition of symbol, though, I’d replace “to represent something else” with “to represent an idea”, which… neatly conjoins both definitions:

A symbol is a sign, shape or object used to represent an idea, while a motif is an idea used many times in a piece of writing.

I’d add one more differentiating point: while a motif must recur in a work (appear many times), a symbol could appear just once or twice.

With that, then, our understanding of symbolism vs motif should be clearer:

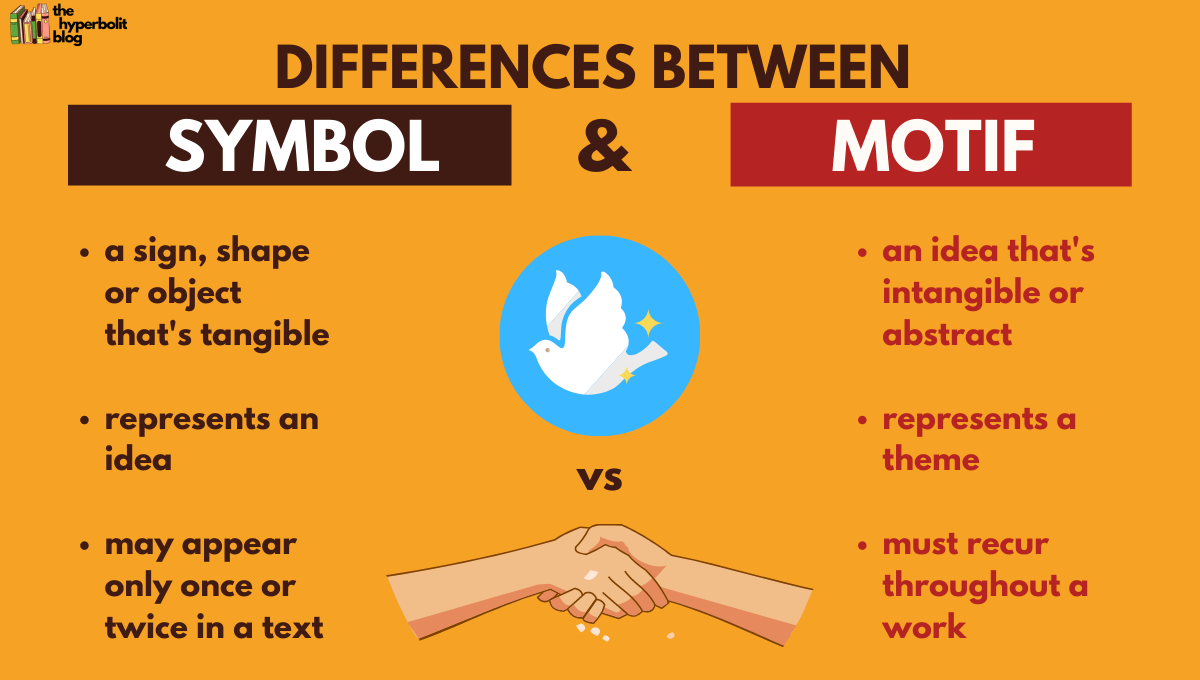

A symbol:

- A sign, shape or object (colour works too) – must be visual or tangible (e.g. a dove)

- Represents an idea (e.g. maintaining peace)

- Could appear only once or twice in a work

A motif:

- An idea – usually abstract or intangible (e.g. maintaining peace)

- Represents a theme (e.g. the importance of peacekeeping)

- Must recur throughout a work

What about symbolism and metonymy?

As I show in this post, metonymy refers to the use of a word which stands in for a related idea. In literary expression, the metonymic ‘word’ usually doubles as a symbol.

To illustrate what I mean by this, let’s build on our dove example in the sentence below –

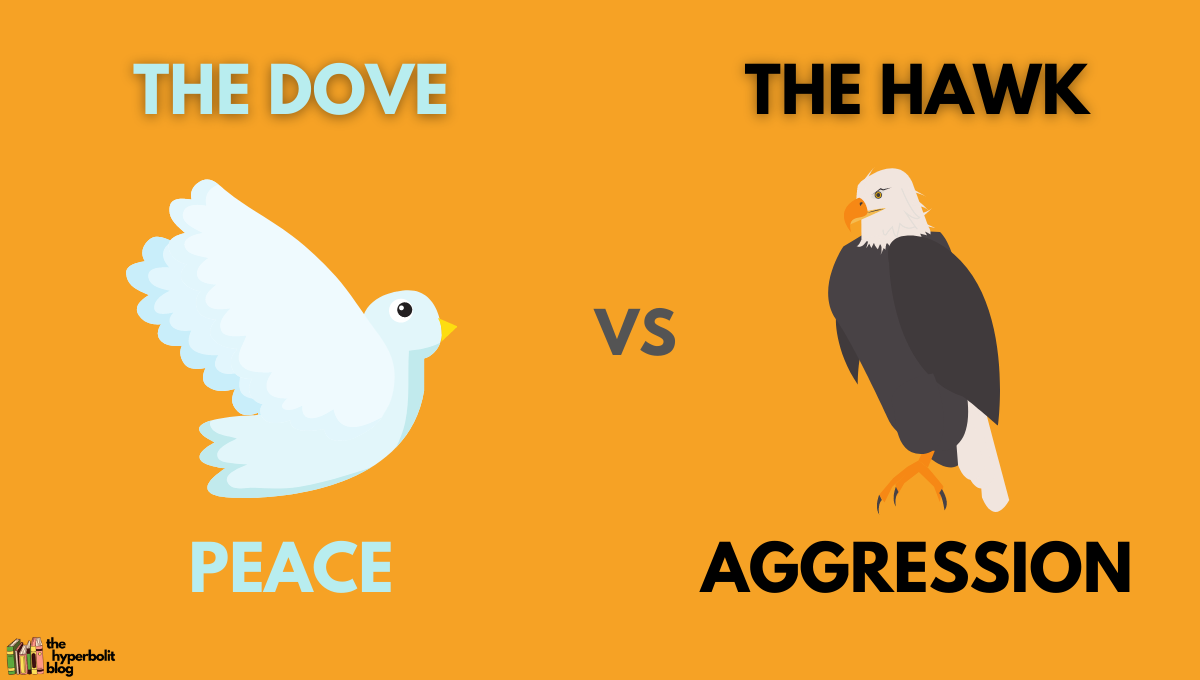

“The negotiating table was divided between doves and hawks.”

We know that the dove symbolises peace-making, while the hawk represents aggression (hence the adjective “hawkish”, meaning ‘supporting the use of force in political relationships’).

As stand-alone items, the dove and the hawk are symbols of peace and aggression.

In the context of my example sentence, however, these two references are used as a direct substitute for the pacifiers and aggressors at the negotiating table.

This means that to tell symbolism and metonymy apart, we need to look at the context:

Is the symbol featured as part of a larger description or narrative?

Or is it being used as a stand-in for its related idea within a sentence?

If the former, then we’re looking at symbolism; if the latter, it’s metonymy.

Now, let’s return to the topic of symbolism vs motif, and examine how they are different in the context of literature.

For this post, my literary petri dish will be William Golding’s Lord of the Flies – a great work of fiction about the timeless tension between good and evil, civilisation and savagery.

... or watch my short animated video below, in which I explain what symbolism is, what examples of literary symbols there are, and how symbol is different from motif:

Have you joined my mailing list yet? You can sign up by clicking on the banner below – it’ll only take you 30 secs:

Reading for motifs in Lord of the Flies: beast from water, beast from air, beasts everywhere

As a dystopian Robinsonade, Lord of the Flies is a pessimistic portrayal of human nature and society.

Man is born evil, and as such, democracy is a fragile institution.

Law, order and civilisation are but thin veneers, under which lie baser, animalistic instincts that we easily give in to.

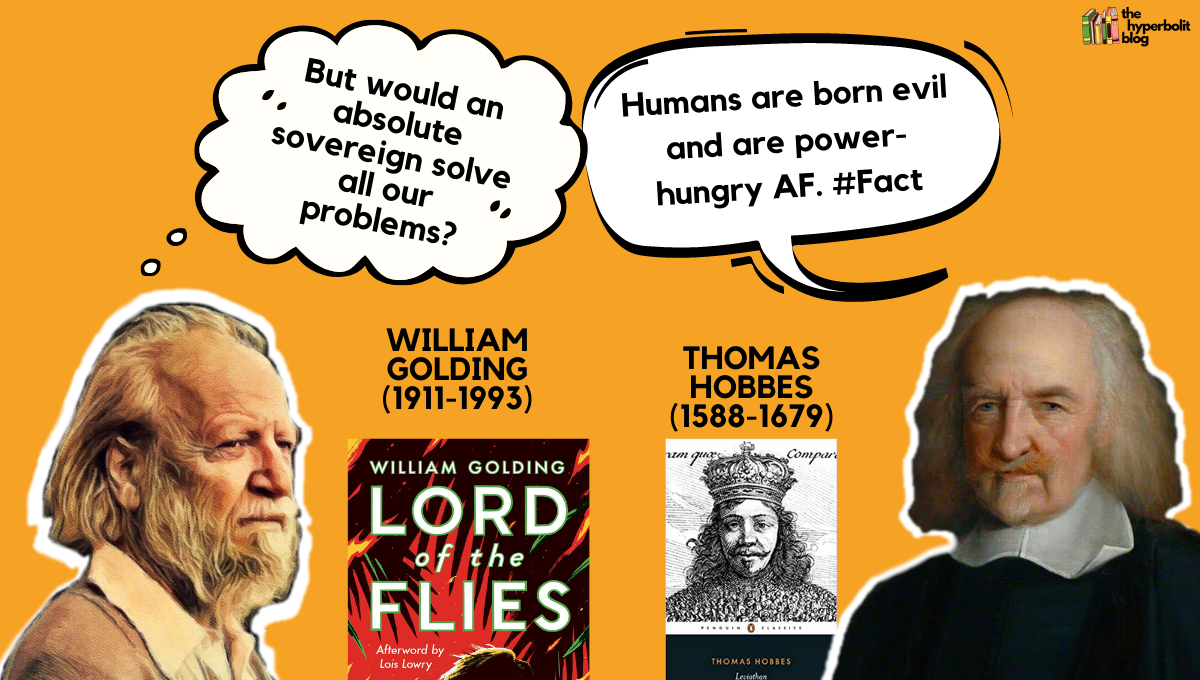

In a way, Golding’s novel both reflects and challenges the Hobbesian view of man, which is that humanity is inherently bad, and therefore requires strong, authoritarian rule for our wayward desires to be kept in check.

But who is this ‘strong ruler’, and if he (or she) is also inherently bad, would society not be just as doomed as it would in a state of anarchy?

In Lord of the Flies, Golding poses this issue through the motif of “the beast”.

What, or who, is this ‘beast’?

Is it a thing?

Or an idea?

An animal, a ghost, or – us?

Throughout the novel, the boys on the island debate, agonise and speculate over what the identity of this ‘beast’ could be, only to become ‘beasts’ themselves in the process, as they descend into fear, irrationality and violence.

This notion of the ‘beast’ also happens to be a key motif in this book, as it’s brought up time and again throughout the narrative, with a presence that spans almost all chapters.

From Chapter 2 onwards, the ‘beast’ is mentioned at least once in each chapter, despite evolving in form and manifestation.

The timeline below highlights some of the key moments in which the ‘beast’ motif appears:

- Chapter 2:

First time the ‘beast’ is mentioned. A boy with a mulberry-coloured birthmark says he saw a “beastie”, “a snake-thing” in the woods (he would later ‘disappear’, presumably burnt to death in the fire). To this, Ralph is sceptical, and insists “But there isn’t a beast!” - Chapter 3:

The boys start getting afraid, and Simon comments that their fear is of the sort that “as if the beastie or the snake-thing, was real” - Chapter 5:

At an assembly, Jack berates the boys for being afraid of the beast. He questions where a beast could possibly come from (“where from?”) and tell them off for being “cry-babies” and scaredy cats. Jack equates the “beast” to “an animal”, which annoys Ralph. Piggy reasons with the boys by telling them that “life is scientific”, which is why there’s no “beast” of the ghostly kind. Phil says he dreamed of “dark and twisty things”, while Percival Wemys Madison suggests “the beast comes out of the sea”. Simon, however, proposes at one point that “maybe there is a beast”, to the anger of many. Others continue to suggest that “perhaps the beast is a ghost”. - Chapter 6:

The title of the chapter – “Beast from Air” – is ironic. The “beast” here refers to the pilot who fell to his death on the island. This suggests that the “beast” is ultimately Man in his fallen state (think Adam and Eve and their fall from Heaven). An important quote in this chapter concerns Simon’s insight about this: “However Simon thought of the beast, there rose before his inward sight the picture of a human at once heroic and sick.” - Chapter 7:

Jack insists that they should go hunt for the beast, but Ralph isn’t convinced. However, they end up going on a “mad expedition”, and ascend the mountain to find “something like a great ape… sitting asleep with its head between its knees” (this is the pilot from Ch 6). As the biological ancestor of man, the ape reinforces the association of human nature with evil. - Chapter 8:

Jack proposes that they should “forget the beast” and focus on the pleasures of hunting. This suggests that when man ignores his capacity for evil, he opens the floodgates to unleash our darker instincts.As Jack and the tribe hunt, they kill a boar and impale its head on a stick. Jack says “This head is for the beast. It’s a gift”. It then ‘speaks’ to Simon in his hallucination, mocking the boys for “thinking that the Beast was something you could hunt and kill”, because “it’s part of you, close, close, close”. - Chapter 9:

Simon sees the ‘beast on the mountain’ for what it is: a dead man. As a result, he realises that “the beast was harmless and horrible; and the news must reach the others as soon as possible”. Taking on the messianic mantle, he is then ‘scapegoated’ for the beast and violently killed by the boys, who descend into a frenzied mob. “The beast was on its knees in the center, its arms folded over its face. It was crying out against the abominable noise something about a body on the hill. The beast struggled forward, broke the ring and fell over the steep edge of the rock to the sand by the water. At once the crowd surged after it, poured down the rock, leapt on to the beast, screamed, struck, bit, tore. There were no words, and no movements but the tearing of teeth and claws.” - Chapter 10:

Despite having killed Simon (who they thought was the ‘beast’), Jack warns the boys to guard against the beast, asking “How could we – kill – it?” He says this because he wants there to be constant target for hunting and an outlet for their violence. But this reference is also ironic; indeed, we can’t kill “it” – if “it” refers to the evil that we’re born with. - Chapter 11:

Ralph erupts in anger and calls Jack “a beast and a swine and a bloody, bloody thief”, which is the most accurate identity ascribed to the beast thus far in the book. Jack, as the representation of evil, is the closest to a ‘beast’. - Chapter 12:

We hear the reference to the “beast” for the final time when Jack and his tribe go after Ralph in their murderous frenzy (“Kill the beast! Cut his throat! Spill his blood!”)

Early on, the boys suppose the ‘beast’ to be “a snake-thing in the woods”, “an animal”, or “perhaps… a ghost”.

The turning point comes in Chapter 6, symbolically titled ‘Beast from Air’, when a pilot falls to his death on the island and ‘assumes’ the elusive identity of this ominous ‘thing’ at the mountaintop.

While the boys lose their civility and capitulate to their moblike instincts, Simon – the quiet, insightful boy – sees this ‘beast’ for what it truly is: the evil that lies within each of us.

Spurred on by the cruel, dictatorial Jack, the boys are eventually consumed by their inner beastliness, as they murder Simon, Piggy, and attempt to kill Ralph at the end of the book.

We see this idea of the ‘beast’ as a perennial concern in the narrative, and it is sustained for the purpose of amplifying one of the central themes of the book – the human potential for evil.

As the concept evolves from the more kiddish understanding of ‘beasts’, such as animals and ghosts, to the more abstract and philosophical view of ‘beast’ as evil, the ‘beast’ idea emerges as a motif.

You’ll notice, then, that ‘a motif’ can be formed of many references (e.g. the 100+ mentions of “the beast” in this book), all of which serve as a kind of structural bunting to shore up the novel’s thematic structure and focalise the reader’s attention on the key message.

Reading for symbolism in Lord of the Flies: the Lord of the Flies

With there being so many possible identities of the ‘beast’, which one is the symbol?

First, if something is a symbol in a literary work, it’s going to get some extended attention from the author – despite only appearing once or twice.

It should also relate to the key theme. In the case of the ‘beast’ motif, then, its corresponding symbol would be the ‘Lord of the Flies’, which is also the “pig’s head on a stick” (Ch. 8) that ‘speaks’ to Simon in his hallucination.

“You are a silly little boy,” said the Lord of the Flies, “just an ignorant, silly little boy.”

Simon moved his swollen tongue but said nothing.

“Don’t you agree?” said the Lord of the Flies. “Aren’t you just a silly little boy?”

Simon answered him in the same silent voice.

“Well then,” said the Lord of the Flies, “you’d better run off and play with the others. They think you’re batty. You don’t want Ralph to think you’re batty, do you? You like Ralph a lot, don’t you? And Piggy, and Jack?”

Simon’s head was tilted slightly up. His eyes could not break away and the Lord of the Flies hung in space before him.

“What are you doing out here all alone? Aren’t you afraid of me?”

Simon shook.

“There isn’t anyone to help you. Only me. And I’m the Beast.”

Simon’s mouth labored, brought forth audible words.

“Pig’s head on a stick.”

“Fancy thinking the Beast was something you could hunt and kill!” said the head. For a moment or two the forest and all the other dimly appreciated places echoed with the parody of laughter. “You knew, didn’t you? I’m part of you? Close, close, close! I’m the reason why it’s no go? Why things are what they are?”

The laughter shivered again.

“Come now,” said the Lord of the Flies. “Get back to the others and we’ll forget the whole thing.”

Simon’s head wobbled. His eyes were half closed as though he were imitating the obscene thing on the stick. He knew that one of his times was coming on. The Lord of the Flies was expanding like a balloon.

“This is ridiculous. You know perfectly well you’ll only meet me down there–so don’t try to escape!”

Simon’s body was arched and stiff. The Lord of the Flies spoke in the voice of a schoolmaster.

“This has gone quite far enough. My poor, misguided child, do you think you know better than I do?”

There was a pause.

“I’m warning you. I’m going to get angry. D’you see? You’re not wanted. Understand? We are going to have fun on this island. Understand? We are going to have fun on this island! So don’t try it on, my poor misguided boy, or else–“

Simon found he was looking into a vast mouth. There was blackness within, a blackness that spread.

“–Or else,” said the Lord of the Flies, “we shall do you? See? Jack and Roger and Maurice and Robert and Bill and Piggy and Ralph. Do you. See?”

Simon was inside the mouth. He fell down and lost consciousness.

(Chapter 8)

The name ‘Lord of the Flies’ is a Christian allusion to Beelzebub, which is referred to as Satan in the four New Testament Gospels.

Literally, Golding’s ‘Lord of the Flies’ is no more than the severed head of a boar impaled on a stick, which Jack had offered as “a gift for the beast” after one of his tribe’s hunting sprees. Symbolically, though, it represents the human urge to externalise our darker instincts and to project them onto outer things, when the source of all that’s problematic lies within ourselves.

Visually, this imagined encounter between “the obscene thing on the stick” and Simon looks rather ludicrous, but that’s perhaps precisely Golding’s intention – to show his readers that what we should most fear isn’t material or external (“fancy thinking the Beast was something you could hunt and kill”), but spiritual and inward, the “part of you” that’s “close, close, close” which embodies our natural desire for power.

It’s ironic, then, that Golding should use a symbol to show us the limitations – and dangers – of erecting symbols, especially when what’s at stake goes beyond the realm of what’s visible.

It’s also interesting to consider why Golding decided to name his novel after its most important symbol.

As a title, ‘Lord of the Flies’ seems to function less as a symbol, and more so a euphemism for what we wouldn’t want to stare straight in the face (or on the cover of a book) – the ‘devil’ in all of us.

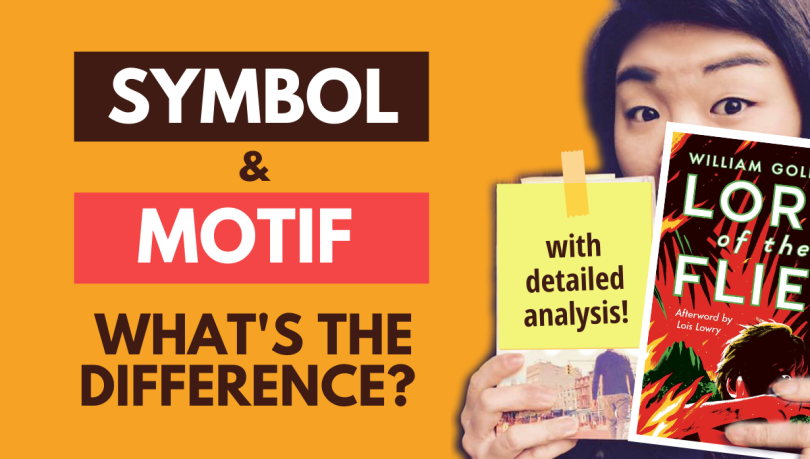

To sum up, then, in Lord of the Flies, we see the distinction and relationship between symbolism, motif and theme played out as follows:

Theme – human evil

Motif – the ‘beast’ (beastliness in our nature and actions)

Symbol – the externalised ‘beast’ / Lord of the Flies / pig’s head on a stick

Hi Jen,

I loved your graphics and the clarity of your images in explaining the differences between the concepts.

I want to use your images in this post as part of a presentation and video to teach my kids in school about symbol and motif.

I will of course credit your work in the video.

Would that be ok with you?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Nicole! Of course, thank you so much for the kind words, and I’m glad you find the resources useful! I post lit learning materials regularly on Instagram (both graphics and videos) – see if that helps you too? https://www.instagram.com/hyperbolit/

LikeLike